China’s Iran Deal Is Just the Beginning

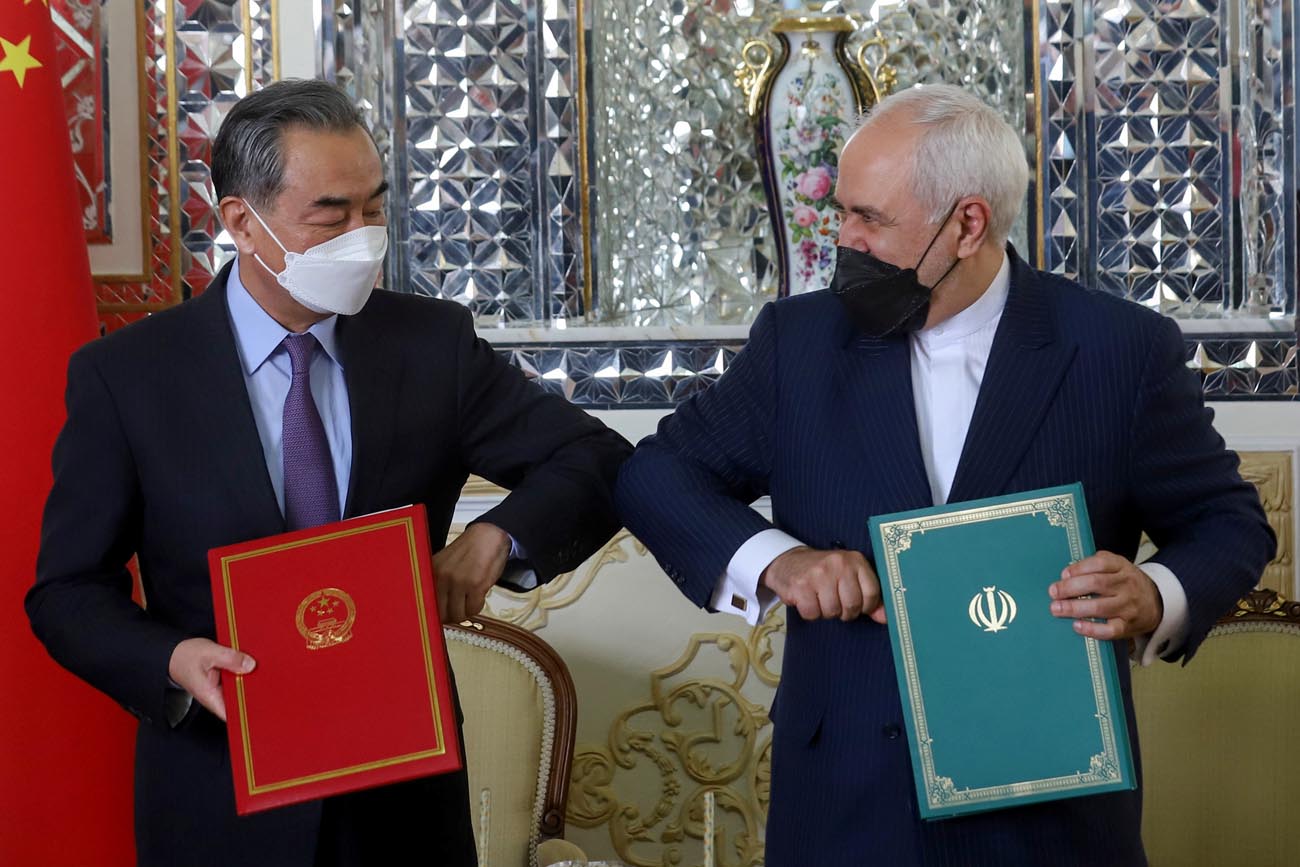

China and Iran recently announced a twenty-five-year “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” which seeks to increase military, defense, and security cooperation between Iran and China, to the consternation of both countries’ adversaries.

The pact does not signal the materialization of an Iran-China alliance but instead points to a broader Chinese strategy to grow its influence in the Middle East. Ironically, this comes at a time when a bipartisan consensus has emerged in Washington that the United States should reduce its engagement in the Middle East to address the challenge posed by a rising China.

The Iran-China deal evinces that the Middle East is an important arena for the emerging great-power competition with China. The United States now needs to prevent China from strengthening U.S. adversaries and gaining predatory influence over U.S. partners in the region.

For the Iranians, the timing of the deal could not be more apropos. Tehran is desperate for cash after U.S. sanctions have crippled the country’s economy and hopes the pact with China will cushion the blow from U.S. sanctions. With China as a supposed purchaser of Iranian oil exports for several decades to come, the Biden administration’s efforts to drag Tehran to the negotiating table will prove much harder.

Meanwhile, China is to gain both oil to fuel its rapidly growing economy and a regional partner that shares its interest in curbing the global reach of U.S. power.

The immediate impact of the deal, thus, might be China unintentionally facilitating further Iranian nuclear enrichment. But its destabilizing effects are unlikely to end there, for China’s interest extends across the region.

In addition to concluding the pact, Chinese foreign minister Wang Li’s trip to the Middle East also included the formation of a regional security plan with Saudi Arabia, a meeting in Istanbul with his Turkish counterpart, and an announcement that the UAE will produce two hundred million doses of China’s Sinopharm vaccine. Meanwhile, Chinese state-owned companies are expanding investments in Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates as part of the Belt and Road initiative.

This increasing pattern of Chinese regional engagement, coupled with generous, if not entirely realistic, promises of foreign investment comes at a time when the United States is reducing and “rebalancing” its presence in the Middle East. Traditional U.S. partners, seeing Iran benefit from Chinese largesse and their own ties to Washington cool, might begin to view China as an increasingly attractive alternative.

China’s activities in the Middle East present a risk to the United States because China plays the field in a wholly realpolitik fashion—it may support America’s enemies (see Iran) or it may court or attempt to court U.S. allies (see Israel). Beijing has no allegiances. It seeks both to strengthen U.S. adversaries or steal its traditional partners.

Washington is not helpless when it comes to containing Chinese influence in the region. The United States needs a deliberate strategy to mitigate China’s quest for greater influence in the Middle East, one that seeks to limit Chinese influence among U.S. partners and thwart Chinese efforts to strengthen U.S. adversaries.

Firstly, Washington should work with its partners to limit Beijing’s access to critical infrastructure, intellectual property, and technologies among U.S. partners. As our organization, the Jewish Institute for National Security of America, recently recommended for Israel, this should include both empowering partners to develop robust oversight regimes for foreign direct investment and exports and offering competitive sources of financing for investment-hungry Middle Eastern firms.

Simultaneously, the United States should recognize it cannot block all Chinese regional economic activity and instead, should encourage China to invest in building the region’s non-critical infrastructure and in firms tackling shared challenges, like global warming.

In dealing with Chinese attempts to build ties with U.S. adversaries, several “soft” tactics also might limit China’s ability to form stable ties with regimes. For example, vis-à-vis Tehran, the United States could launch a combination of cyber, information, and psychological operations centered on revealing privately held internal tensions between the Chinese and Iranian governments, which might include pointing out China’s horrific genocide of its Uighur population and the hypocrisy of the Muslim regimes that tolerate it.

On the information side, a plethora of voices have criticized the ambiguity and secretive nature of the negotiating process, and the United States should amplify those voices across various international outlets. A coordinated campaign of this nature would help to undermine the sincerity of the pact and, in turn, the ability of each party to rely on each other in the long term.

As Beijing deliberately pursues a balance of power in the region to rival Western countries, the onus will fall on the Biden administration to challenge China’s Middle Eastern machinations, which range from intervening with America’s traditional partners to emboldening U.S. adversaries. The China-Iran deal is just the tip of the iceberg.

Erielle Davidson (@politicalelle) and Ari Cicurel (@aricicurel) are senior policy analysts at the Jewish Institute for National Security of America’s Gemunder Center for Defense and Strategy.

Image: Reuters