The Hail Mary of Power-Sharing in Afghanistan

In a multi-ethnic nation such as Afghanistan where all other types of autocracy have failed, a democratic and decentralized system of governance is perhaps the only remaining option.

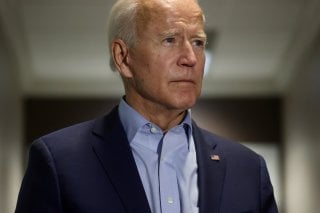

Power-sharing with the Taliban is a concept at the heart of the Biden administration’s new strategy for Afghanistan, as it seeks the rapid formation of a new coalition government in an upcoming summit in Turkey. But the very notion strains credulity. Apparently, people are to believe that the group that took Afghanistan back to the stone ages in the 1990s, that then harbored and protected the perpetrators of 9/11, and that remains deeply in bed with al Qaeda will voluntarily form a new interim government with some elements of President Ashraf Ghani’s administration, or other Afghan political and civil society leaders—at precisely the moment when the United States, and thus NATO, seem ready to leave the scene.

Yet President Joe Biden’s idea sounds better than another ten or twenty years of forever war, in which government forces slowly but inexorably lose ground to extremists, while foreign forces try to stanch the bleeding. Biden seems half inclined to pull U.S. troops out of the country this year, partly out of frustration with Ghani’s approach to previous peace talks with the Taliban.

What to Do?

The best approach is to test both sides with concrete proposals for power-sharing. With the best of luck, they will then begin to compromise themselves, though the process may be slow. But even if that is not possible, then the reactions of the Taliban and the government will show us more about which side is trying harder for peace. Even in the absence of a successful deal, that could help Biden decide whether U.S. forces should stay or go. If the Afghan government shows more sincerity in the quest for peace than the Taliban, especially at first, then that will suggest that foreign forces should further delay their departure.

So, by what formula could a fundamentalist and autocratic Islamist movement really share power with a group of political and civic leaders devoted to democracy and individual rights?

Start with the most central issue of all, security. How would the Afghan army and police forces collaborate with the other side—that is, the current enemy? Answering this question incorrectly could produce a coup if an extremist winds up in charge. Or it could lead to civil war and chaos if the security forces fall apart under bad and contested leadership.

We would suggest a multi-step process of building a single unified Afghan security force. It should begin by freezing in place existing government and Taliban forces under a general ceasefire. Each could patrol along and within its own lines of authority. Regional coordination centers involving Taliban and government officials would oversee the operations—laying the groundwork for a long-term merger of the various “kandaks” into a national-guard-like system. As the ceasefire took hold, international military forces could complete their departure from Afghanistan, provided that Al Qaeda forces were not invited to return by the Taliban and provided that Taliban sanctuaries in Pakistan were being shut down.

The arrangement would probably need to be monitored by a UN observation team, perhaps made up entirely of personnel from Muslim-majority countries. Rather than fund just the Afghan army and police, as is the case today, the international community could pay stipends to both sides, provided that the UN team could certify compliance (including with the Pakistan sanctuary issue).

Then there is the matter of sharing political and legislative and budgetary power. Under the 2004 Constitution, the president is very powerful. This must change. Otherwise, the winner-take-all competition for who will be the next president will doom the peace talks from the start.

In the central government, the parliament must be strengthened, and a prime minister position should probably be created as well. Then, there would be three official centers of power: the president, the prime minister, and the speaker. One of the first two positions might be selected by an Ulema Council so as to ensure religious involvement in the government; the first such official could be a member of today’s Taliban leadership. The others, along with members of parliament as is the case today, would be elected. Any new law would need the support of the legislative and executive branches of government. Even hardcore Pashtun nationalist parties such as Afghan Milat are entertaining this kind of idea for a stronger parliament today, so it does not come out of the blue.

Still, these reforms will likely leave the Taliban with less overall power in Kabul than they expect or demand. The solution is not to hand them more, but to let them compete for it politically at the local level as well, as suggested by scholars such as Laurel Miller of the International Crisis Group as well as many Afghans. Direct elections for governor and mayor positions could be held. Education could be supervised locally. Funds for schools and other government activities could be allocated directly to local governments, and not disbursed or withheld by Kabul as a way of demanding loyalty. This approach would give the Taliban incentive to try to win over local populations—not by brute force, or extremist ideology, but by the quality of life that it can help make possible, even if its vision would have a very conservative and Islamist bent.

Several options exist for the legal system, which is today in shambles. A parallel court system may work, especially in light of the fact that customary law is already common in many regions of Afghanistan as a substitute or an alternative to official law. For example, there could be a sharia-based court based on foreign models and a civil court. Citizens would generally be free to choose which court system to use; in the event of disagreement between litigants, local authorities could decide.

Over time, these various political reforms will give the Taliban incentives to transform into a political movement rather than a jihadist one. Even if it were a strong-arm political machine with various antidemocratic aspects, the international community’s financial resources would create some leverage to keep its behavior within bounds.

In a multi-ethnic nation such as Afghanistan where all other types of autocracy have failed, a democratic and decentralized system of governance is perhaps the only remaining option. It also may be the only idea that both Ghani and the Taliban could accept since neither truly considers the other legitimate.

Most likely, neither the government team nor the Taliban will endorse these kinds of tough steps towards peace right away. Both think (probably wrongly) that they have the upper hand in any talks. Putting real ideas before the two delegations and observing how they react and respond is the most promising way available to us right now to test the waters—and, if we are lucky, to jumpstart the actual negotiation process itself. Meanwhile, if the Ghani government shows at least some flexibility, as seems likely, the United States and NATO should signal that their forces will stay until a deal is struck. To do otherwise would almost surely defeat any prospects of persuading a caliphate-minded Taliban that it really must rethink past ways and reach a compromise.

Omar Sharifi is a professor at the American University of Afghanistan.

Michael O’Hanlon is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Image: Reuters.