How Spies Spread the Myth of China’s Peaceful Rise

A new book persuasively details how sophisticated influence operations helped popularize the idea of China’s “peaceful rise.”

For decades, Communist China has operated under Deng Xiaoping’s famous dictum to “hide your strength and bide your time.” Now that the mask is off and the United States and its allies are belatedly waking up to the threat posed by Beijing, a question looms: how did so many experts and policymakers get China’s rise wrong? As Alex Joske highlights in his new book, Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World, part of the answer can be found in Beijing’s influence operations.

Little is publicly known about China’s spies. Joske, who worked as an analyst for the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, hopes to remedy this. And, in an easily digestible volume, he succeeds in offering a glimpse into little-discussed aspects of Beijing’s intelligence methods.

Many books on China’s spies focus on industrial espionage or high-profile cases like Larry Wu-tai Chin, a Chinese spy who worked for the U.S. Army and the CIA for nearly forty years. Spies and Lies, however, examines how Beijing utilizes spies to shape narratives and influence policymakers.

Joske uses a wide variety of sources, including memoirs, old court cases, interviews with retired intelligence officers, and a great deal of internet sleuthing, to highlight and expose how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has deceived the world. What emerges is a profoundly disturbing story.

China employs a dizzying number of intelligence agencies. The Ministry of Public Security (MPS) and the People’s Liberation Army have intelligence components, but it is the Ministry of State Security (MSS) that tends to attract the most attention. Popular perception, Joske notes, has it that the MSS is aggressive but unsophisticated. Yet this couldn’t be more wrong.

The MSS plays the long game, identifying and courting policy and opinion makers. Direct recruitment and overt approaches are often eschewed. Rather, the MSS and its various front organizations prefer a light touch. As a result, they can often evade attention from law enforcement and counterintelligence authorities, many of which are chiefly concerned with industrial espionage and attempts to steal trade secrets. Although discreet, the MSS is stunningly bold.

Indeed, China’s influence operations, Joske documents, are “widespread, targeted and handled with direct involvement from Party leaders.” Beijing’s most stunning success was the effort by the MSS to “convince influential foreigners that China would rise peacefully and gradually liberalize.”

In November 2003, a CCP official named Zheng Bijian gave a widely disseminated speech calling for China’s “peaceful rise.” It was precisely what many foreigners wanted to hear. China wasn’t seeking great power confrontation; it didn’t want to challenge the U.S.-led liberal international order. Rather, it just needed to be accommodated. No less an authority than Henry Kissinger praised Zheng’s peaceful rise narrative as a “quasi-official policy statement.”

But as Joske illustrates, this was largely a ruse, an influence operation run by MSS-connected organizations. “The very vehicle Zheng hung his hat on, and which enabled his promotion of the narrative, [the] China Reform Forum, was simply an MSS-controlled front group that had selected him as its latest figurehead.” Indeed, the very address that the China Reform Forum used in government registration records “is the same location once used by two magazines and two front groups controlled by the MSS Social Investigation Bureau.” From its beginning in 1994, “this think tank was a staging ground for influence operations.”

The CCP-manufactured narrative of a “peaceful rise” was broadly accepted. The West was more than happy to believe what it wanted to believe—a key feature in an influence operation.

Of course, many of the luminaries associated with MSS-linked front groups and individuals didn’t know that they were being used by a Chinese intelligence service to disseminate disinformation. And, as Joske amply illustrates, such operations were pervasive, crossing political lines. Naturally, all this aided their effectiveness.

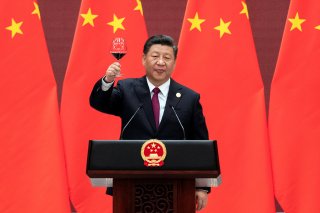

And by deceiving key Western elites, Beijing was able to build its strength and bide its time. That time, current CCP head Xi Jinping seems to believe, is now at hand. But all is not lost; there are lessons to learn.

Joske not only highlights how the West got it all wrong but also offers recommendations for what should be done.

First, there’s an inbuilt tendency for many to avoid addressing influence operations. As Joske observes, “a career minded counterspy would have to be stupid to dedicate their efforts to chase influence operations that almost never lead to prosecutions.” After all, the long-term costs of such operations are seldom immediately apparent.

Additionally, MSS influence operations often involve political and financial elites—hardly people that intelligence agencies would want to potentially embarrass in investigations. And most counterintelligence agencies are more focused on protecting state secrets or warding off industrial espionage; MSS operations at think tanks and foreign affairs conferences are, at first glance, not as damaging.

Second, there are many longstanding myths about China’s methods of spying that, while frequently employed, don’t withstand scrutiny. For example, it was long thought that China used a “thousand grains of sand” approach to intelligence gathering. “The central claim of this theory,” Joske notes, “is that China relies on ad-hoc masses of ethnic Chinese amateurs to steal huge amounts of low-grade information, with relatively little involvement by professional spies and intelligence agencies.” But as Spies and Lies documents, this assumption is false and leads to overlooking, minimizing, and misunderstanding China’s tactics.

There is also a dearth of information about China’s spy agencies and methods. Given the subject, this is to be expected. However, open-source methods can help offset this disadvantage—as Joske himself illustrates.

“Educating the public about the CCP’s political influence methods and narratives should be a priority,” he concludes. His debut book does just that. One hopes that policymakers and journalists, from Washington to Canberra and beyond, read it.

Sean Durns is a Washington, D.C.-based foreign affairs analyst. His views are his own.

Image: Reuters.