How Britain Lost the War It Never Wanted with Iran

London is paying the price for America's problems.

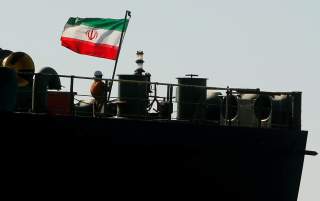

Authorities in Gibraltar have released an Iranian oil tanker they had been holding since July 4, breaking the ice around a long diplomatic standoff between Iran and the United Kingdom. But the story isn’t over yet, as U.S. authorities are still hounding the tanker in a crusade to cut off all Iranian oil exports.

A court in the British overseas territory of Gibraltar allowed the Grace 1 to leave on Thursday, and rejected a last-minute legal filing on Sunday that would have allowed U.S. police to take custody of the Iranian ship. British marines had originally stormed the tanker as it passed through the Straits of Gibraltar, based on an accusation that the ship was headed to Syria in violation of European Union sanctions.

Gibraltarian authorities said that they released the Grace 1, now called the Adrian Darya 1, based on a promise that it would not go to Syria. But a spokesman for Iran’s foreign ministry denied that Iran had promised Britain anything in exchange for the Adrian Darya 1.

“What we have announced publicly was simply a statement of the truth of the destination of the Grace 1, which from the beginning was not headed to Syria,” Seyyed Abbas Mousavi said in a statement to Iranian journalists.

“We support Syria in all matters, including oil and energy,” he added. “The Islamic Republic sells its own oil to whatever customers it wants, old or new.”

But just before the Adrian Darya 1 was set to leave Gibraltar, the U.S. Department of Justice unveiled a warrant for the ship’s seizure “based on violations of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), bank fraud statute, and money laundering statute, as well as separately the terrorism forfeiture statute.”

The department’s August 16 press release accused the Adrian Darya 1’s operators of plotting “to support illicit shipments to Syria from Iran by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a designated foreign terrorist organization.” The Trump administration declared the IRGC a terrorist group on April 8. Barbara Slavin, director of the Future of Iran Initiative at the Atlantic Council, said that this was the first time the United States had put sanctions on the military of a sovereign country.

It is unclear who owns the Adrian Darya 1. Gibraltar confirmed in an August 18 press release that “the U.S. disclosed to the Gibraltar [Central Authority] various elements that indicated that the IRGC controlled the Grace 1 and its cargo.”

However, the authorities refused to accept the U.S. warrant, citing “differences in the sanctions regimes applicable to Iran in the EU and the U.S.” and EU laws “protecting against the effects of the extra-territorial application of legislation adopted by a third country” in an August 18 press release.

“It is to be noted that the IRGC is not a designated foreign terrorist organisation in Gibraltar, the U.K. or in the EU generally, unlike in the U.S.,” the Gibraltarian press release explained.

Under a legal principle called “dual criminality,” the crimes listed in the U.S. complaint would also have to be crimes under British law in order for Gibraltar to hand over the Adrian Darya 1. “Some of the charges relate to money laundering and fraud,” said Erich Ferrari, a Washington-based attorney who specializes in sanctions law. “Maybe they thought, well, those are crimes in this jurisdiction, so that’s our hook for dual criminality.”

“Other countries have in the past just extradited or followed the [United States’] lead, even where the proposed extradition or arrest was on shaky legal grounds,” he told the National Interest. “They wanted this to get done. They might not have had the most solid of legal grounds, but they took a shot for it anyways.”

“It’s completely in line with what the U.S. has increasingly done for the last twenty-five years, in which it’s essentially trying to argue that U.S. law applies everywhere,” said Trita Parsi, executive vice president of the Quincy Institute. “These countries are essentially afraid of saying no. In this case, Gibraltar stood up to Trump, which is interesting.”

“What happened now was essentially was the Brits realizing, there’s no win for them in this. They’re going to end up taking the brunt of the Iranian anger,” he told the National Interest. “The biggest surprise to me is, why did the UK go along with this in the first place? It was difficult to see how this in any way, shape, or form would have ended well for them.”

Britain claims that local authorities made the decision to seize the Grace 1 on their own, but Spanish officials say that the United States was reaching out to Spain about the tanker at the time. About two weeks later, Iranian forces captured the Stena Impero, a British tanker, in the Persian Gulf. Iran claimed that the Stena Impero was violating maritime law, but Iranian officials had been threatening “reciprocal action” over the Grace 1.

By “making Grace 1 the poster child for sanctions enforcement,” the U.S. and UK governments “probably anticipated that the Iranians would respond in kind and capture a UK tanker,” said Henry Rome, an analyst on Iranian and Israeli politics at the Eurasia Group. “Washington and London probably calculated that seizing Grace 1 was worth it—especially because it provided a constant reminder to the international business community of the risks of doing business with Iran.”

Parsi believes that the lack of a U.S. response to the Stena Impero incident convinced the British to change their calculus. “The U.S. is enlisting these allies to do its dirty work for it, but when they end up getting pushback from the Iranians, the U.S. is not there to back them up,” he said.

It is unclear whether Iran will release the Stena Impero in exchange for the Adrian Darya 1. But for now, British authorities do not seem to be pressing the matter.

“Diplomatically and politically, the sentiment in Europe is still pro-deal, and is still anti max pressure,” said Behnam Ben Taleblu, a senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, referring to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Under the 2015 agreement, Iran surrendered its nuclear research program to international inspections in exchange for protection from economic sanctions.

President Donald Trump, who had denounced the accord as a “bad deal,” imposed sanctions on Iran in May 2019 as part of a new “maximum pressure” campaign aimed at cutting all Iranian oil exports. Since then, Iran and the United States have come to the brink of war, with Trump ordering and then cancelling an attack on Iran after a June 26 skirmish between Iranian air defenses and a U.S. surveillance drone.

The Adrian Darya 1 has left British custody, but the United States could still attempt to seize the ship before it reaches its final destination. But physically attacking the tanker is “too risky and would risk a significant response from Iran,” Rome told the National Interest.

An escalating fight over the Adrian Darya 1 could be a boon to hawks in the Trump administration. “The [Iranian] response, [National Security Advisor John] Bolton calculates, I assume, will push Trump into a corner in which he has to take military action,” Parsi speculated.

But the United States could instead use “creative political, legal and economic measures” and “a combination of threats and inducements” to keep the Adrian Darya 1 homeless on the high seas, said Taleblu.

“How can the U.S. use ‘lawfare’ to make sure that this vessel, which left Gibraltar, does not have a home in any country in the Mediterranean basin, and cannot dock anywhere, and cannot offload that oil, and cannot allow Iran to get paid for that oil?” he asked. “Ultimately, that move could send a stronger signal against Iran.”

“There’s sanctions for dealing with respect to certain sectors of Iran’s economy. So there could be a lot of different ways and authorities that could be implicated to impose sanctions,” Ferrari explained. “Some of the language [used by the Department of Justice] gives off the impression that, because of the IRGC’s role in the Iranian economy, almost anything you do with Iran is criminalized.”

On August 15, the U.S. Department of State announced that “the U.S. government intends to revoke visas” for “[c]rewmembers of vessels assisting the IRGC by transporting oil from Iran.” And on August 19, U.S. officials reported warned authorities in Greece, where the Adrian Darya 1 is scheduled to arrive by Sunday, that assisting the tanker is considered support for terrorism under U.S. law.

Rome, however, is skeptical at the success of this campaign. “[T]he plan backfired in the Gibraltar courts,” he said. “Now the ship and its oil are back on the high seas, and the U.S. is left with issuing bland diplomatic statements urging countries not to let it dock at their ports.”

Matthew Petti is a national security reporter at the National Interest and a former Foreign Language Area Studies fellow at Columbia University. His work has been published in Reason and America Magazine.