Kamala Harris’s Possible North Korea Policy: Ready for the Threequel?

With more breathing room for Pyongyang in the “new Cold War” and its stronger refusal to denuclearize, Harris, following Biden’s presidency, will find it extremely difficult and politically unrewarding to pursue new initiatives on North Korea.

On August 20, 2024, there was a commotion at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) in Seoul. Just one day before, the U.S. Democratic Party had unveiled a new party platform, outlining Team Harris’s policy priorities ahead of the 2024 Democratic National Convention (DNC). Notably absent from the new platform was any mention of the denuclearization of North Korea.

A similar omission had occurred in the Republican Party platform a month earlier. Unsurprisingly, this raised alarm in Seoul, prompting the MoFA spokesperson to reassure the public that the U.S. commitment to North Korean denuclearization remained “steadfast.”

What should we expect from President Kamala Harris on North Korea? While making predictions in politics is generally unwise, the Harris case appears to be an exception. We’ve already seen the future twice: Barack Obama’s “strategic patience” and Joe Biden’s “calibrated practical approach.”

President Harris will likely introduce a catchy name for her policy, but it will essentially be a carbon copy of her two Democratic predecessors. Two factors suggest this threequel: the deepening new Cold War and Pyongyang’s steadfast refusal to denuclearize.

Pyongyang is Not Frozen in this New Cold War

First, the emerging new Cold War is providing more breathing room for North Korea. The U.S. unipolar moment was a difficult period for Pyongyang. With the Soviet Union gone and China focused on its economic development, North Korea was pushed into a tiny corner, receiving little assistance beyond occasional Chinese support. However, as China began to assert its global aspirations and the United States refused to accommodate them, the resulting strategic competition between the two evolved into a new Cold War, creating openings for North Korea.

Additionally, the Ukraine war has offered Pyongyang opportunities to strengthen its relationship with Moscow. The popular rhetoric in Washington against the “authoritarian axis” resonates well in Pyongyang. During the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) session in September 2023, Kim Jong-un emphasized a triangular alliance between Pyongyang, Beijing, and Moscow to counter the “Asian version of NATO” formed by Seoul, Washington, and Tokyo.

The tiny corner to which North Korea was once confined is now expanding.

Second, North Korea has solidified its resistance to denuclearization. Kim arrived at the Hanoi summit with little to offer. He was open to negotiating about only the nuclear facilities at Yongbyon, while the rest, such as secret uranium enrichment programs (UEP) and hidden nuclear weapons, remained off the table.

Given that a secret UEP had previously undermined the 1994 Agreed Framework, Kim’s offer at Hanoi was a nonstarter for Washington. Since the failure of the Hanoi talks, North Korea has bolstered its de facto nuclear power status. During the Party Congress in 2021, North Korea declared itself a “nuclear weapon state.” At the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) in September 2022, Kim enacted a “new nuclear law,” emphasizing the “irreversible” nature of his nuclear arsenal.

Later, during the Central Committee session of the Workers’ Party of Korea in December 2023, he authorized the use of nuclear weapons, “to suppress the whole territory of South Korea” in the event of conflict. North Korea is rapidly distancing itself from the idea of denuclearization.

The Three Democrat Musketeers

With more breathing room for Pyongyang in the “new Cold War” and its stronger refusal to denuclearize, Harris, following Biden’s presidency, will find it extremely difficult and politically unrewarding to pursue new initiatives on North Korea. In a speech supporting Harris, Obama remarked that “the sequel is usually worse,” referring to Trump’s bid for a second term.

Unfortunately, Harris is likely to be the threequel when it comes to North Korean policy. On September 29, 2022, Harris made a one-day visit to South Korea. Despite a tight schedule, she managed to visit the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone), where she touted the U.S. alliance with South Korea. Her otherwise well-choreographed trip was marred by a gaffe in which she mistakenly praised “the U.S. alliance with North Korea.”

Meanwhile, North Korea welcomed her visit in its own unique way, by firing missiles both before and after her arrival. This episode encapsulates what likely lies ahead for the Harris administration: nice words with little interest from Washington and occasional provocations from Pyongyang.

About the Author

Hyung-min Joo is a professor in the Department of Political Science & International Relations at Korea University. He received his Ph.D. in political science from the University of Chicago. Before joining Korea University, he taught at DePaul University. Since 2012, he has been a North Korea expert with the V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) project. He has also served on policy advisory committees for the Ministry of Unification and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His research focuses on comparative theory, communism, North Korea, the shadow economy, and power/resistance. His recent publications include “The Shadow Economy and Social Change in North Korea” in Asian Studies Review (2024), “What We Murmur Behind Their Backs: Hidden Transcripts of the North Korean Ruling Elite” in Problems of Post-Communism (2023), and “Everyday Authoritarianism in North Korea” in Europe-Asia Studies (2021).

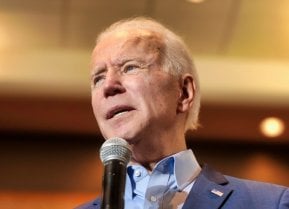

Image Credit: Creative Commons and/or Shutterstock.