China Studies the Contours of the Gray Zone

Beijing strategists go to school on Russian tactics in the Black Sea.

There is good news out of Ukraine, for once. A fresh face, Volodymyr Zelensky, won the presidency back in April with a resounding victory. Ukrainian nationalists have been thrown back on their heels, and the Zelensky wave seems to have been confirmed in the parliamentary elections. The young president, short on experience but possessing impressive wit, now has the mandate to make difficult decisions that could pull Ukraine in a more stable, peaceful, and prosperous direction if these efforts are not derailed by the recent seizure of a Russian tanker.

A Chinese strategic assessment of contemporary Black Sea security offers us a glimpse of the impact Russia’s actions have had. There is a reasonably high degree of similarity between Russia’s position in the Black Sea and China’s situation in its own “near seas,” especially with regard to the South China Sea. Beijing has been watching with admiration and has been effectively “taking notes” on Russian actions in the delicate region since 2014–15 and even before that time. It is not simply that China could opt for a lightning Crimea-like annexation of Taiwan (although it might), but also that China has been observing so-called “gray-zone tactics,” or military actions with major political effects that are beneath the threshold of all-out war.

The rather detailed rendering appeared under the headline “A Farce: What can be said about the detention of the Ukrainian patrol boats [场闹剧: 从乌克兰巡逻艇被口说起]” in the naval magazine Naval and Merchant Ships [舰船知识] in early 2019. The Chinese analysis opens with a crisp description of how infrastructure—a Chinese specialty after all—can alter strategic facts on the ground (and the water too). Of course, the Crimean Bridge [克里米亚大桥] which was partially completed in 2018, links Russia directly to Crimea and also, it is observed, “chokes” the entrance to the Sea of Azov. For the ongoing war in eastern Ukraine, the port of Mariupol is identified by the Chinese author as crucial, so that the control of the Kerch Strait is assessed to be highly significant. Thus, this analysis concludes that Moscow’s completion of the Crimean Bridge in May 2018 constituted a “heavy blow” against Kiev.

Not surprisingly, the Chinese rendering seems to track closely with Russian accounts. It is reported that the group of three Ukrainian vessels (two artillery boats and a tug) were taken under observation by Russian forces at 4 p.m. on November 24, 2018. At 9:30 p.m., this account has the Russian side warning the Ukrainian squadron that requests to transit the Kerch Strait require a twenty-four hour advanced notification. At 5 a.m. on November 25, it is asserted that the Ukrainian request to transit the Kerch Strait was rejected by the Russian side. At that point, “the Russian side discovered that the Ukrainian artillery boats raised their guns to aim at the Russian ships, which was taken as a threatening action [俄方发现乌方两艘炮艇炮口升起并指向俄舰被视为威胁性举动].” Low on fuel, according to this rendering, at 6 p.m. on November 25, the Ukrainian squadron suddenly went to flank speed to attempt passage under the bridge, according to the Chinese telling.

At 8:55 p.m., and after two explicit warnings, this account has the first shots fired by a Russian vessel against one of the Ukrainian artillery boats. “Three seconds later, the boat requested Russian assistance, saying there were wounded, and a few seconds after that, the boat was detained.” After ramming, the tug was also captured. Finally, this Chinese account has the other artillery boat fleeing, but surrendering when confronted directly by a Kamov-52 attack helicopter at 9:52 p.m. By 6:40 a.m. on November 26, the three captured Ukrainian ships were said to be berthed in the Russian port of Kerch, with twenty-three Ukrainian sailors made prisoners. It is noted in this Chinese analysis that “six wounded … were delivered by the Russian side to the hospital.” Needless to say, this version has more than a few discrepancies with the most widely circulated Western accounts.

Yet, rather than chewing over the details of the Kerch skirmish for us here, it's important to understand the lessons that Chinese strategists have taken from what transpired. It’s a fair bet, albeit admittedly speculation on my part (informed by a visit I made there about a decade ago), that this Kerch Strait incident is already a case study being analyzed and taught at the Chinese Coast Guard Academy in Ningbo, and probably in China’s many naval academies, as well. To be sure, the Russian Coast Guard comes away with a burnished reputation, having prevailed in this “first ‘real combat’ [第一次’实战’]” on the seas between Russia and Ukraine. Not surprisingly, the Type 22460 modern Russian cutter comes in for praise. These 630-ton vessels are both well-armed and also fast with decent endurance as well. The Chinese article observes that Moscow has already built more than a dozen of these boats in the last decade for a total fleet that will reach perhaps thirty boats as production continues. It is noted with some pride that at least one of this class is outfitted with a Chinese-made diesel engine. The parallels evident in the simultaneous buildup of coast guard fleets by both Beijing and Moscow are amply evident and this set of events may well be viewed as confirming evidence for China’s decision going back at least a decade to build the world’s largest armada of coast guard ships.

The Ukrainian fleet does not get similarly high marks. While the fifty-four-ton artillery boats are reported to be the most ambitious Ukrainian military shipbuilding project since independence, it is also observed here that it was not the Ukrainian Navy that put down the first orders for these slightly odd boats. Rather, it is said to have been U.S. aid money to actually fund a third country’s naval forces (Uzbekistan). Never mind that somewhat bizarre use of American taxpayer funds, the Chinese assessment of the Ukrainian artillery boats is that they are not seaworthy and can only really be used effectively in conditions of moderate or preferably calm sea state. Moreover, it is stated that these Ukrainian vessels are poorly armed. Their “threat to any normal warship is very small [对普通战舰的威胁很小].”

To be sure, this Chinese analysis emphasizes the importance of the powerful Black Sea Fleet (BSF) in the background of these events “to respond in the event of escalation.” It is widely understood that Moscow has long prioritized this particular fleet and they have received many new ships and substantial modern weaponry, up to and including even Russia’s first deployed hypersonic anti-ship missiles. Yet, it is interesting that the Chinese article focuses not on hypersonic weaponry and such, but rather on the workhorses of naval warfare, such as the ASW corvette, Suzdaletz [Суздалец], which was said to be nearby during the Kerch incident. Indeed, the article writes extensively regarding the exploits of this small 1980s-vintage Russian warship. That naval vessel, it is explained, was apparently part of a BSF task force that engaged the small navy of Georgia in the August 2008 conflict. “The Georgian Navy was thus destroyed [格鲁吉亚海军就这样覆灭了].”

The article also briefly discusses the Russian actions in early March 2014 to seize most ships of the Ukrainian Navy. The article takes a special interest in the employment of special operations forces for that task. Such efforts were undoubtedly also facilitated by complex identity issues related to armed forces personnel serving on Crimea. Could identity issues play a similar role in Chinese “gray zone” operations? That possibility can hardly be ruled out.

Still, appraising all these developments over the last decade or so in the Black Sea, this Chinese analysis concludes rather starkly: “In the past ten years, Russian maritime forces have lifted the butcher’s knife to the former Soviet republics three times, while the latter have offered no resistance to the slaughter. [十年间, 俄罗斯海上力量三次对前苏联加盟共和国举起屠刀, 而后者几平无任何反抗能力, 任其宰割].” The article ends by remarking that Russia is succeeding in converting land power into sea power, and that Crimea has been converted into a “bastion” as a key part of that project.

A simple takeaway from this article that Beijing is carefully monitoring and looking to imitate aspects of Russia’s “gray zone” coercion strategy. Interestingly, this description also notes certain “soft” aspects of Russian coercion in the Kerch incident; for example, the fact that none were killed and wounded were taken immediately to the hospital for treatment. Still, the clear emphasis in the analysis is on both the special operations and especially the coast guard aspects of these events.

What is to be done? It is all too common among foreign-policy elites these days to opine that “the United States and its allies are not moving fast enough to counter efforts by Russia and China to foment instability with ‘gray zone’ tactics,” as the New York Times did in its July 22 editorial. However, that bit of conventional wisdom regrettably refuses to admit why China and Russia continue to tally a steady stream of victories in the nebulous world that comprises “gray zone” operations—namely that space for military or quasi-military action below the threshold of major war. The reasons are twofold and reasonably simple.

First, Beijing and Moscow both wield very considerable and indeed credible combat power in these proximate domains. That is simply the nature of fighting along interior lines, as any strategist knows. Second, and even more importantly, both of these great powers have the will to “go to the mat” to control (or nearly so) the outcomes of brush-fire conflicts on their borders. For Americans, the stakes are much murkier, to say the least, and may even approach the absurd. The double asymmetry, in both military capabilities and the will to use them, therefore constitutes “trumps” and means that Russia and China will continue to roll.

Does that mean that Washington needs to redouble its efforts, sending suitcases of cash to build up the Ukrainian and Philippine navies and coast guards, etc.? No. Such efforts to date have regrettably made these tense situations worse. A more mature and realistic strategy would recognize that spheres of influence cannot be wished away with soaring rhetoric, nor can the stark reality of the balance of power (or lack thereof). An essential part of the United States learning to live in a multipolar world will be the admittedly difficult task of adapting American diplomacy and defense strategy to this new set of circumstances.

Lyle J. Goldstein is Research Professor in the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) at the United States Naval War College in Newport, RI. In addition to Chinese, he also speaks Russian and he is also an affiliate of the new Russia Maritime Studies Institute (RMSI) at Naval War College. You can reach him at [email protected]. The opinions in his columns are entirely his own and do not reflect the official assessments of the U.S. Navy or any other agency of the U.S. government.

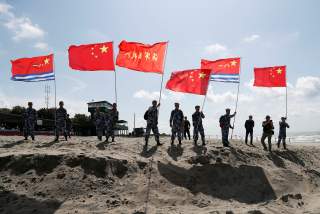

Image: Reuters