Where did the Modern Mercenary Industry Come From?

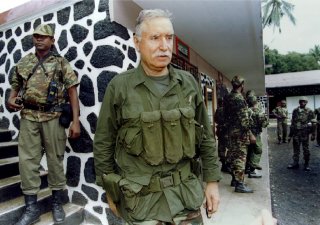

Meet the father of modern mercenary warfare.

But Denard, who fled to South Africa after Abdallah’s death, later told a French court he was in the president’s bedroom when Abdallah’s personal bodyguard, Abdallah Jaffar, burst into the room and fired at Denard. Abdallah was hit by accident. Denard said he shot back and killed the assailant.

“I was a soldier,” Denard said tearfully. “I was never a killer,” he told the court.

Said Mohamed Djohar, former head of the Comoros Supreme Court, succeeded the slain Abdallah and ruled until 1995, when he was overthrown by … Denard, again, out for one last adventure.

That time, French troops swooped in to restore order. The old dog of war Denard, née Bourgeaud, was arrested and jailed. He died of Alzheimer’s in Paris in 2007, at the age of 78. The truth concerning that bloody November night died with him.

The same year that Denard died, one of his former lieutenants, a man who had served under the self-styled warlord as an officer in the Comoros presidential guard in 1985, flew to Mogadishu, where he was to fulfill the destiny denied Denard.

Richard Rouget, a.k.a. “Colonel Sanders,” was 47 years old when he helped conquer an African nation with the full but largely unspoken support of the U.S.

Rouget fought for his own personal gain. But America was happy to benefit. And it didn’t hurt that almost no one called Rouget a “mercenary.” Decades after Denard’s bloody heyday, mercenaries had learned to go by other names.

Contractors.

Guns for hire

In the late 1990s, there was a seismic shift in the way governments waged war in Africa and across the globe. Bob Denard’s bloody antics in the Comoros had established a precedent.

Men like Denard but perhaps a little less theatrical—many of them South Africans—took the next logical step. They founded businesses with boring-sounding names but a deadly purpose: to fight Africa’s nastiest conflicts on behalf of corrupt, inept governments, and for profit.

They found willing customers in governments and international organizations increasingly unwilling to, or incapable of, waging war alone—inhibitions that only deepened following the Somalia bloodletting.

“In the post-Cold War era … this cross of the corporate form with military functionality has become a reality,” security expert P. W. Singer wrote in Corporate Warriors. “A new global industry has emerged. It is outsourcing and privatization of a 21st-century variety, and it changes many of the old rules of international politics and warfare.”

In 1989 former South African commando Eeben Barlow, a lanky, hook-nosed man with one blue eye and one green one, founded Executive Outcomes, a U.K.-based company offering security training services to the South African military and businesses. Barlow was in his mid-30s at the time. For five years he was Executive Outcomes’ sole employee.

Then, in March 1993, Angolan rebels seized Soyo, a major state-owned oil facility on the country’s lawless coast. The Angolan army was busy battling rebels elsewhere, so the government approached Barlow with an offer the former commando could not refuse: $80 million to oversee the liberation of the captured oil facility.

Barlow quickly assembled a strike team of 50 of his old Special Forces colleagues. With Angolan helicopters flying top cover and two chartered Cessnas shuttling in supplies, the Executive Outcomes strikers assaulted Soyo.

In a week of hard fighting, the mercenaries liberated the facility. Three of Barlow’s men were wounded.

The Angolan government was impressed. In June they offered Barlow an even more lucrative contract to train up an entire army brigade to fight the rebels. For this task, Barlow recruited 500 former South African commandos and chartered a small air force, including 727 jets.

Executive Outcomes’ responsibilities gradually expanded. Soon the company was also providing pilots for Angola’s Russian-made helicopters, propeller-driven attack planes, and MiG-23 jet bombers.

In November the Angolan brigade Barlow’s men were training attacked the rebels, initiating what would be an 18-month campaign fought in equal parts by Executive Outcomes and its Angolan trainees, but with the South African company providing all the expertise and air power.

The Angolan brigade was a front for a mercenary army. Two Executive Outcomes aircraft were shot down and several employees were killed.

The battered rebels sued for peace and in January 1995 Barlow pulled his men out of Angola. They were not idle for long. The government of Sierra Leone, under pressure from rebels of its own, was Executive Outcomes’ next client.

In April, a hundred of Barlow’s mercs, led by a South African ex-commando named Duncan Rykaart, flew into the tiny coastal country in a chartered 727. Their plan: to evict the rebels from the capital Freetown and the country’s diamond fields, then locate and destroy the rebel headquarters.

Again with native troops fronting and Executive Outcomes’ aircraft in support, Barlow’s fighters advanced. A year later the rebels sued for peace.

Riding high, Executive Outcomes alongside another security firm began negotiations with Mobutu Sese Seko, the dictator of the Congo facing a determined rebellion led by Laurent Kabila. “Neither firm took the contract, as the regime was on its last legs,” Singer wrote.

Instead, Executive Outcomes waited until after Mobutu fell … and signed a contract with Kabila, now president of the Congo and facing rebellions of his own. In a daring operation, Barlow’s commandos captured the strategic Inga dams. But Kabila failed to pay up, and so Executive Outcomes abandoned Congo, leaving Kabila and his ragtag army to fight on alone.

In the wake of Executive Outcomes’ successes, so-called “private military companies” sprouted like weeds. Nowhere were they thicker than in South Africa. The government in Cape Town moved to regulate the merc companies, and in 1998 Executive Outcomes folded. Its chief officers went to work for other PMCs or founded companies of their own. “Rather than truly ending its business, it appears EO simply devolved its activities,” Singer wrote.

Rykaart joined NFD, a security company with strong ties to Executive Outcomes and which was allegedly helping the Sudanese government in its battle with U.S.-allied southern rebels.

Later, Rykaart worked in American-occupied Iraq for Aegis Defense Services. In 2009, while working in Somalia for yet another security company, he was killed when the plane he was riding in crashed shortly after takeoff.

The company’s name was Bancroft Global Development. Among its roughly two- dozen mercenaries was Richard Rouget, former lieutenant of Bob Denard in the Comoros.

Private war

If the bush wars of the 1990s sparked the explosive spread of private security companies, then the U.S-led invasion and subsequent eight-year occupation of Iraq starting in 2003 was fuel poured directly on the fire.

“In the early days of the Iraq war, there weren’t enough troops,” Steve Fainaru explained in his book Big Boys Rules. “As the situation deteriorated, a parallel army formed on the margins of the war: tens of thousands of armed men, invisible in plain sight, doing the jobs that couldn’t be done because there weren’t enough troops.”

In just the first 18 months of the war, the U.S. government spent $766 million on security contracts with private companies. The governments of Iraq and various U.S. allies added untold millions to the total.

In July 2005 the Government Accountability Office estimated there were at least 60 major security companies operating in Iraq with 25,000 employees. In those first two years of the war, no fewer than 200 contractors died in combat.

It was apparent that the Pentagon could no longer—or would no longer—fulfill its national security responsibilities without the assistance of mercenaries. That raised some profound questions. Not the least of which: accountability.

On Sept. 16, 2007, private soldiers from Blackwater, a North Carolina firm that provided security for the State Department, gunned down 17 civilians in Nisoor Square in Baghdad.

The mercenaries later claimed they had come under attack, but the U.S. Army found no evidence of insurgent fire. “The incident almost certainly would have been buried but for the sheer number of people whom Blackwater killed,” Fainaru wrote.

The Iraqi government protested. Blackwater attempted to settle the issue with payments to victims’ families. In the U.S. criminal and civil suits were filed. At least one of the shooters got off on a technicality. Another pleaded guilty to manslaughter and agreed to cooperate with investigators.

As of late 2012, four cases were still open, with the defendants facing manslaughter and weapons charges. Blackwater was barred from Iraq but held onto its State Department contract. The company changed its name twice in an attempt to distance itself from the killings.

The Nisoor Square shootings shone a light on the shadowy world of security companies but did nothing to reverse the trend towards more and more corporate involvement in America’s wars. Nor did the killings and the subsequent legal cases necessarily resolve the confusion over accountability.

At worst, a few of Blackwater’s employees could go to prison for manslaughter. But the business itself survived and even thrived, as did other companies like it.

“Public militaries have all manner of traditional controls over their activities, ranging from internal checks and balances, domestic laws regulating the activities of the military force and its personnel, parliamentary scrutiny, public opinion and numerous aspects of international law,” Singer explained. Security companies, he added, “are only subject to the laws of the market.”