A Russian-Chinese Partnership Against America?

China and Russia consider themselves great powers, and there is agreement in both Beijing and Moscow on cooperating to limit or constrain America’s ability to dominate international relations and challenge their sovereignty.

Beijing and Moscow are critical of U.S. dollar dominance in the global economy and are increasingly trading goods via barter arrangements or using national currencies. The U.S. dollar still accounts for 80 percent of all global transactions, but in 2019 only 51 percent of Sino-Russian trade was in U.S. dollars; this declined to 46 percent in the first quarter of 2020. Chinese trade and the renminbi are becoming increasingly important for Russian firms that since 2014 have sought to avoid U.S. sanctions and the possibility of being excluded from the swift financial messaging service.

Possible sources of tension in Russian-Chinese economic relations include China’s increasing presence in Central Asia, Russian arms sales to India, Chinese trade and investments in Belarus, and Beijing’s growing engagement with Mongolia through the China-Mongolia-Russia-Economic Corridor. For the past two years, Beijing has pressured Hanoi to shut down an offshore oil project between PetroVietnam and Rosneft, claiming at least one of Vietnam’s exploration blocks fell within China’s Nine-Dash Line. Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi reportedly asked Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov to lean on Rosneft to abandon the project, but his Russian counterpart declined. So far, however, the two countries have avoided clashing openly.

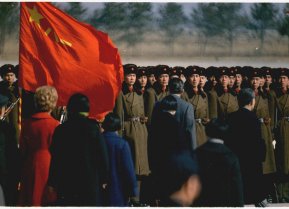

U.S. SANCTIONS and confrontational posturing have encouraged defense cooperation, including arms sales (China is the second-largest purchaser of Russian weapons), regular joint military exercises, and naval maneuvers. However, arms sales as a proportion of total bilateral trade have declined dramatically since the 1990s. Military exercises are an important component of the relationship but are more likely to signal support for each other’s sovereignty, security, and regional territorial disputes than serve as rehearsals for future joint operations. Moscow and Beijing jointly oppose U.S. anti-ballistic missile systems deployments in Eastern Europe and East Asia and are increasingly challenging America’s freedom of navigation (FON), with the result that the U.S. Navy dramatically ramped up its FON operations in 2019.

Russia and China understand and accept the need of the other to exercise regional hegemony in areas critical to their national security—for Russia, this is the post-Soviet space along its western and southern borders; for China, the western Pacific (especially Taiwan and Hong Kong). Both countries have security interests in Central Asia, and while Moscow and Beijing have worked together through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, their interests are not fully harmonious in this region. Tensions could rise here as China augments its economic and military posture in the region.

Russia and China do not have a formal defense treaty, and it seems unlikely they will conclude one in the near future. Each wants to keep options open and not be dragged into a conflict that is not in their national interest. Still, at the 2020 Valdai Discussion Club, Putin stated that while Russia was satisfied with the current state of relations a formal military alliance with China could be imagined in the future. Even without a formal alliance, the two countries tout a close partnership that involves expanding trade, arms sales, regular military exercises, intelligence sharing, and sharing military technologies.

Russia does not have the military capability to challenge the United States in the Indo-Pacific, and the same can be said of China in Europe. However, each regards the United States as their chief competitor, and their relationship is described as a “strategic partnership” meant to balance American military power. This constrains U.S. operations in Eastern Europe and the Western Pacific, even if Moscow and Beijing do not formally coordinate their actions. As Hal Brands and Evan Montgomery point out, the United States is ill-prepared for opportunistic aggression—having to deal with regional challenges from both powers simultaneously. These conflicts could involve military force, but in the current environment, some form of hybrid action is more likely. The Sino-Russian partnership may not be a full-blown military alliance, but it is a de facto non-aggression pact that ensures China faces no land threat, and so is free to be more assertive along its periphery and at sea. Similarly, should a conflict break out between China and the United States in the South China Sea or over Taiwan, Russia might take advantage of the opportunity to destabilize Poland or the Baltic states. These scenarios may not be likely, but they are within the realm of possibility if we consider the relatively low costs of information or “hybrid” forms of aggression, coercive diplomacy, or obstructionism in the un Security Council.

AS IN trade, Russia and China have certain complementarities in technology. Key joint projects are planned in aviation and aerospace, nuclear reactors, drone technologies, communications, artificial intelligence, and supercomputers. Putin has revealed that Russia is helping China develop an anti-missile early warning system, while Lavrov has stated that in contrast to the United States, Russia will cooperate with China and Huawei to introduce 5G technology in Russia. Reportedly, Huawei is planning to quadruple research and development personnel in Russia over the next five years and anticipates working with Russian universities, research institutes, and the broader scientific community on artificial intelligence, information, and communication technologies. Huawei is also planning to invest up to $800 million in developing Russia’s digital infrastructure over the next five years. Many of these technologies are dual-use, with both civilian and military applications.

China’s technologies are cutting edge and cheaper than those developed in the West, making them attractive to Russian businesses and government agencies. U.S. and European “smart sanctions” that target Russian energy and military sectors provide additional incentives for Russian-Chinese cooperation in the high-tech field. However, the Kremlin has developed an ambitious domestic program for developing scientific research in mathematics, climate science, genomics, and robotics. Russia currently spends only 1 percent of its GDP on research and development, well behind other high-tech leaders like South Korea, Germany, Japan, and the United States, and only half of China’s allocation. Cooperation with China may help Russia improve its record in scientific research, but national pride—and strategic considerations—militate against excessive reliance on Chinese technology.

China and Russia agree on the need for cyber sovereignty and promote the concept within the United Nations; they reject the concept of internet freedom as promoted by the United States. The two authoritarian states are cooperating in developing technologies such as facial recognition software and internet blocking tools that improve the state’s ability to censor and control information, monitor dissidence, and repress individual freedom, and both supply surveillance gear to countries around the world. However, some tensions are apparent in technological cooperation. In August 2020, for example, a leading Russian Arctic scientist was charged with supplying classified information on submarine detection to Chinese intelligence services. Moreover, Russia and China appear willing to cooperate on cyber defense, but they do not appear to be coordinating their efforts offensively. In short, Russia and China will likely continue to cooperate on technology, but as with trade and economics, Russia occupies the junior position in the relationship.

SINGAPORE’S MASTER statesman Lee Kwan Yew once observed that as China rose, a stable balance of power in the Asia-Pacific would depend on America and Japan maintaining an isosceles triangle, where U.S.-Japanese ties remained closer than either Sino-Japanese or Sino-American relations. Today, a version of 1970s triangular diplomacy has returned; this time, Russia and China are far closer to each other than to the United States. This relationship, however, is not equilateral, but rather a “skinny” isosceles triangle with Russia as the very narrow base.

America no longer occupies the swing position in the power triangle as it did in the 1970s and 1980s. Moscow may eventually decide that it needs to align with the United States to balance a much stronger China, but that is not likely in the foreseeable future. Russia and China have many common interests, and the areas where their interests clash are few and manageable. The strategic partnership is not likely to weaken over the next few years, and may well strengthen, though it probably will not result in a full-blown military alliance. Russian-Chinese trade will likely increase over the next five years, albeit gradually, and we can expect China to ramp up investments in key areas. Energy will remain central but diminish as a share of bilateral trade. Neither Russia nor China is about to reverse course and fully buy into a liberal international order under U.S. leadership, assuming a post-Trump America attempts to reestablish global hegemony.

The Sino-Russian relationship is asymmetric, but for now, that does not appear to be a problem. Russian leaders understand their country’s junior position in the partnership, and they will strive to keep the relationship on an equal footing, though this may become increasingly difficult. For now, Beijing is careful to treat Russia with respect as a fully co-equal partner, but that could change as China becomes more confident of its global position.

The United States has benefited from having shaped the postwar international order, and its leading position has served the country well over the past seven decades. Abandoning globalization and major international institutions in favor of an isolationist position will merely put the United States at a further disadvantage vis-à-vis China and Russia. U.S. resources have been stretched thin by COVID-19, and the political dysfunction in Washington combined with deep divisions in America’s political culture have eroded the country’s post-Cold War hegemony.