Afghanistan Headed for Financial Collapse, Former Bank Chief Warns

If that happens, the Taliban will have little choice but to turn to China for support.

Ajmal Ahmady, the former director of Afghanistan’s central bank, Da Afghanistan Bank, warned that the country would enter a period of prolonged financial decline if the Taliban failed to institute economic reforms on Friday.

At an Atlantic Council event, the finance minister underlined that the Taliban “had sufficient revenues to run an insurgency, but not to run a government.”

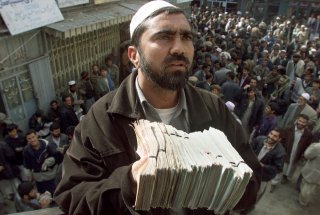

While the country’s currency, the afghani, has remained relatively stable since the Taliban occupied Kabul on August 15, this has largely been because of difficulties in exchanging afghanis on the world market. Business activity in Kabul remains subdued following the takeover, with some sources indicating that merchants are wary of running afoul of the group’s rules.

The Taliban’s government has largely been unable to access the finances of its predecessor. When the group entered Kabul, the country’s central bank was largely empty, with former President Ashraf Ghani accused of taking $170 million in cash with him into exile—a claim that Ghani has vigorously denied. The country’s assets in the United States were also frozen, and funds that the International Monetary Fund and World Bank had promised Kabul were put on hold. More ominously, four-fifths of the prior Afghan government’s budget came from the United States, which has made it clear that it will not continue to extend those funds to the Taliban. Ahmady suggested that Afghanistan’s GDP would decrease by 10 to 20 percent over the coming year, describing the future months as an “extremely challenging or difficult economic situation” but falling short of a total collapse.

While the Taliban has traditionally gained revenue from the drug trade—ninety percent of the world’s heroin originates in Afghan fields—the group has publicly committed to eradicating drugs within the country, a promise that, if kept, would represent another major reduction in its revenue. The group briefly abolished the drug trade in 2000, during its last period of rule, and poppy cultivation sharply decreased. However, after the U.S. invasion and the collapse of the first Taliban government, the group returned to drug trafficking as a way to fund its insurgency.

In the Taliban’s current iteration, its spokesmen have emphasized more traditional means of revenue, notably including the extraction of Afghanistan’s vast and largely untapped mineral wealth. Taliban officials have reached out to China for trade and investment and received a largely positive response in Beijing, which seeks to add Afghanistan to the country’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Trevor Filseth is a current and foreign affairs writer for the National Interest.

Image: Reuters