Beware of Chinese Hegemony

China is starting to mold its patron countries into its own image of authoritarian capitalism.

Amidst misguided campaigns to make the world safe for Western liberal democracy, the global community has forgotten that authoritarian countries, too, are guilty of hegemony. Soon after Russia’s October Revolution, the Comintern billed itself as the savior of post-colonial societies looking to emerge into modernity from the yoke of Western exploitation. The price for such delivery? Adopting a Soviet system of government.

China is in danger of reviving that tradition of exporting its take on authoritarianism. Granted, its methods are much more subtle. In place of the Soviet demand for twinning, China requires loyalty in matters of foreign affairs, which often means foregoing true democracy. The country has (sincerely) insisted that, unlike the West, it is opposed to interference in the internal affairs of others. However, a bet that China will succeed in bringing about true multilateralism where the Pax-America order has failed will prove to be a fantasy.

Last month was the culmination of China’s yearlong announcement that it will take up its own mantle of global governance. Since the lead-up to the APEC summit, Beijing has rolled out a veritable alphabet soup of multilateral organizations to challenge the much-maligned preeminence of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization.

China’s most credible claim to leadership is in the area of infrastructure development. Not surprisingly, the most developed of its multilateral initiatives is the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Twenty-one countries have subscribed to the $50 billion bank to make a dent in Asia’s $3 trillion infrastructure funding need. Significantly, South Korea and Australia did not join due to American and European diplomatic pressure. The Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific, China’s bid to transform Asia into the EU lite, met with even more intense resistance. Still, the APEC nations have agreed to explore the idea.

Nor Beijing is neglecting alliance-building outside of Asia. The New Development Bank (more commonly known as the BRICS bank) was established earlier this year and is the most mature of China’s multilateral engagements outside the region. Beijing is also actively building silk roads to Central Asia, East Africa, the Middle East and Europe to facilitate trade and investment. Even the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, an anti-terror security body comprised of Central Asia and China, is looking to expand and strengthen economic ties between its members.

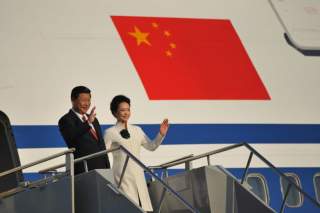

In its new leadership role, China is promising it will avoid the traps of Western multilateralism. Namely, it will not demand that countries meet conditions for financial aid that disregard local input and circumstances. In a key foreign policy speech given late last month, Chinese President Xi Jinping rebuked the Western order and pledged that China will “respect the independent choice of development path and social system by people of other countries."

This is obviously pretense. First, China’s overseas development projects to date have often disregarded local considerations. True, its bilateral investments have filled a gap where developing countries in Latin America and Asia fail to meet the free-market, liberal requirements of organizations like the IMF and WTO. For example, the China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank provided approximately $110 billion to developing countries in 2009 and 2010. Latin America received $79 billion from these two Chinese banks from 2003 through 2011, far outpacing the World Bank’s $57 billion. Africa, the largest beneficiary, has reportedly received approximately $170 billion in foreign investment over the last nine years. () While avoiding the political chaos and economic instability of Western-style globalization, many Chinese investment projects have nevertheless led to vast local environmental destruction. Unemployment remains untreated or worsens since China prefers to use its own workers. Local laws and regulations may remain untouched, but Sinification persists.

Second, even without explicit economic coercion, China is starting to mold its patron countries into its own image of authoritarian capitalism. This is especially pronounced in Central Asian governments, particularly the regimes of Nazarbayev’s Kazahstan and Karimov’s Uzbekistan. And despite their democratic ambitions, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Venezuela Argentina and many other recipients of Chinese dollars are all leaning towards statist models of development.

Most importantly, China’s largest foreign policy goal is to realize the China dream. Echoing Xi, Li Keqiang, China’s premier, has stated that China must pursue the “strategic goal of achieving the great renewal of the Chinese nation.” While many Asian countries are still happily signing trade agreements with the Middle Kingdom, they remain concerned about a return to the Imperial tributary system. The emperor rarely interfered, but there was an understanding that China was owed deference and political loyalty.

To be sure, China's ambitions should be encouraged if the calculus that much of the developing world has made is correct. Economic development comes before any other considerations. Being part of the Beijing sphere of influence is a small price to pay if it means importing the success of the China model.

The devil, however, is in the local details. Whatever large-scale trade agreements are agreed upon in principle, the individual member nations determine implementation. It is eminently sensible that they would want a voice in how economic investments will be used. Their fears of losing sovereignty will not be assuaged simply because a new global power is at the helm.

China has already begun to discover this with the BRICS bank. Despite being far and away the largest economy in that acronym, China made many compromises unbefitting its relative stature to share decision-making control with the others. It remains to be seen whether China will have to make similar concessions with respect to its newest multilateral ventures. While there is room for optimism given the early stages, China should beware the temptation to believe it can succeed where its Western counterparts have tried and failed.

Rebecca Liao is a corporate attorney, writer and China analyst based in Silicon Valley. Her writing has appeared in Financial Times, Foreign Affairs, The Atlantic and Bloomberg View, among various other publications. She tweets at @beccaliao.

Image: Flickr/APEC 2013/CC by 2.0