The Huge, Strange Coalition Opposed to an Obama Apology at Hiroshima

Food for thought...

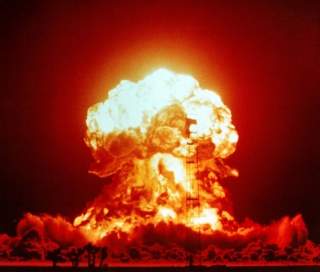

Later this month, President Obama will attend the 42nd G7 Summit in Ise, Japan, about half-way between Tokyo and Hiroshima. Following John Kerry's visit to Hiroshima in early April, the first ever by a sitting US Secretary of State, many speculate that Obama will do the same and could in fact apologize for the atomic bomb drop of August 1945. Kerry apparently found his Hiroshima visit harrowing, and it fits with Obama's less blustery approach to US foreign policy that he would consider an expression of remorse, perhaps akin to his address to the Muslim world in Cairo in 2009.

But if the politics of that speech were contested, this would be worst, as almost no one wants it.

U.S. Conservatives:

It is a populist article of faith in the US that the bomb-drop was necessary; I do not remember this even being controversial in any textbook I read until my senior year of college. Veterans groups and public opinion were powerful enough to shut down a major exhibit on the 50th anniversary of the bomb drop in 1995, and no serious public figure I can think of talks about this. Hiroshima is even less controversial than Dresden.

So it is not hard at all to imagine the huge backlash Obama would face at home from Republicans, neoconservatives, talk radio, Fox News, veterans groups and so on. That this is an election year only worsens the calculus. Donald Trump has fractured the Republican party, but if there is one thing all Republicans agree on, it is that Obama is 'weak.' A favorite conservative critique is that Obama apologizes for the US, and a Hiroshima apology would be easily spun as another stop on Obama's 'apology tour.' Were Obama to do this, it would be an election season gift to the struggling GOP, and Hillary Clinton would find herself answering questions on this for weeks. Honestly, this alone is probably enough to derail any Obama effort.

China and the Koreas:

Similarly, it takes little imagination to see how badly this would provoke China and the two Koreas. Memories of the Pacific War run deep, and resistance to Japan in that conflict are central legitimizing narratives in all three countries. The communist parties of both China and North Korea were tested in the crucible of that war, and the nationalist credibility both earned from having fought the Japanese justified their post-war take-overs. Even today, both continue to use Japan as a villain for nationalist and state-building purposes, with their constant insistence that Japan must remain disarmed and that any military build-up on its part is a precursor to renewed Japanese imperialism. The standard World War II narrative suits these two just fine; indeed, it is still quite alive for both of them today.

An apology to Japan by the major contributor to its defeat would throw the moral economy of North Korean and Chinese post-colonial anti-Japanism into doubt. Not only would it suggest that anti-Japanese forces in the war did awful things too, a US apology would explicitly recognize how far Japan has come from the Axis imperialist of the 1940s to today's liberal, human rights respecting, global governance cooperating democracy. China and North Korea are none of those things of course. It suits neither Pyongyang nor Beijing to see Japan rehabilitated; ghosts of the 1940s are preferred as politically useful strawmen.

Worse, the anti-Japanese struggle narratives of the North Korean and Chinese communist parties are highly exaggerated. Kim Il Sung and Mao Zedong did far less to defeat the Japanese in their countries than, respectively, Chiang Kai Shek and the Red Army of the Soviet Union. Mao and Kim were quite content to free-ride on these forces, which of course can never be admitted. So any major re-examination of the war's end, which such an apology would provoke, is unwanted.

Given that South Korea is a democracy, one might have expected a different course. But there too, Japan-as-villainis deeply politically inscribed. The issue of who collaborated with Japan during the colonial period is hugely divisive and continues to roil the country 70 years later, as does the fate of the comfort women. South Korean analysts too tend to see Japanese re-armament as a pre-cursor to imperialism, and there is deep resistance to seeing Japan as rehabilitated or deserving of apologies for wartime events. That Japan cannot quite seem to admit to itself that it started a truly awful conflict only hardens the resistance to apologies to the erstwhile colonialist and imperialist.

Japanese Conservatives (yes, really):

One might imagine the nationalist community in Japan to most seek such an apology, but as Jake Adelstein notes, there is little interest there too. A US apology would have domestic ramifications Americans are likely unaware of, but for the Japanese conservatives trying to make Japan a more 'normal' partner of the US, the apology would only help the domestic left's effort to hold onto Japan's unique pacifist, semi-isolationist foreign policy.

Specifically, an Obama apology would revive discussion about the conflict from which the Japanese pacifist position draws its political and moral strength. Japanese conservatives want to look forward to tension with China or North Korea to justify a more robust military, not back to a time when the Japanese military rampaged around the region. And an apology by the war's victor only strengthens pacifist arguments on the futility of the use of force: even in WWII, the 'good war,' the good guys acted badly, suggesting that the use of state violence always leads to immorality.

This, curiously enough, aligns with America's long-time interest that Japan carry a greater burden in the alliance and generally do more, leading to the bizarre outcome that an American president doing this to show America's maturity would be acting against US interests.

Reconciliation vs Zero-Sum Politics:

Obama's impulse to apologize is morally laudable. As a student of Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela, he sees that reconciliation and trust-building are achieved in part through the mutual recognition of error and inappropriate violence. Obama, unlike so many Americans, seems willing to recognise that even the US has done some pretty awful stuff (if he wants an even greater challenge, consider how the US should reckon with the fate of Native Americans). There is in fact a pretty good case that the bomb drop was unnecessary.

But humility is rare in international politics, intellectually dominated as it is by nationalism, grievance-pandering, prestige-seeking, and demands for recognition. While US and Japanese elites may embrace this post-modern, post-national ethos, that does not apply in modernist, nationalist East Asia where an apology will be read as just another turn in enduring regional competition.

This piece first appeared in the Lowy Interpreter here.