Western Civilization's Life Coach

Mini Teaser: A new survey of Western thought begins in bombast and ends in triviality.

Arthur Herman, The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization (New York: Random House, 2013), 704 pp., $35.00.

ALBERT EINSTEIN is said to have recommended that “everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” It is an injunction that Arthur Herman would have been well advised to heed when he embarked on the writing of his latest book, The Cave and the Light. But then oversimplification has been at the heart of Herman’s enterprise from the outset. Anyone who has already extruded works such as The Idea of Decline in Western History, To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World, Gandhi and Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age, Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II and How the Scots Invented the Modern World is clearly not someone in whose imagination either nuance or complexity can be assumed to occupy much psychic space. Instead, Herman is a serial extoller, a panegyrist whose attention is periodically seized by one great man (Winston Churchill or Senator Joseph McCarthy, upon whom he lavished an admiringly revisionist biography) or a great people (the Scots) or a great institution (the Royal Navy, American business), which he then presents as the explanatory key to the success and dynamism of the Western world, even if we epigones in the West no longer necessarily understand our own great intellectual, moral, political and technical inheritance.

Even by Herman’s own grandiloquent standards, however, The Cave and the Light is in a class of its own. It is a monument not to the importance of historical thought but to his own hollowness. He begins in bombast and ends in triviality. He is a self-appointed life coach for Western civilization.

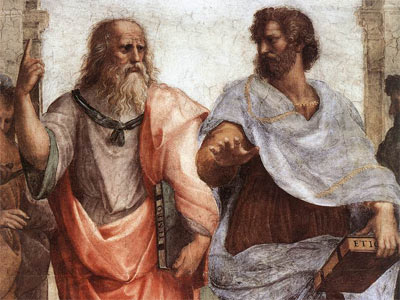

AT THE OUTSET, he asseverates, “Everything we say, do, and see has been shaped in one way or another by two classical Greek thinkers, Plato and Aristotle.” That such wisdom constitutes little more than the conventional thought inculcated in nineteenth-century British public schools does not seem to trouble Herman unduly. This is in part because his project is to refute those in the contemporary West who, in his telling, dismiss these thinkers as “dead white males” and the classics as having no future. Herman at times in his book takes a break from his breathless romp through Western history and philosophy to settle scores real and imagined with the global Left—in this case, the cynical teaching assistant’s tag for History 101, “From Plato to NATO,” is literally accurate. But while he is a political conservative (currently a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute) and an admirer of both Friedrich Hayek and Ayn Rand, even he might have thought twice about the “grandeur that was Greece, glory that was Rome” approach.

This is where the second part of his thesis comes in, the one already limned in his book’s subtitle, where Herman posits that the conflicts in Western civilization ever since ancient Greece have their roots in the dichotomy between Aristotle’s vision of what he calls “governing human beings” and Plato’s philosopher-king. To be sure, Herman’s heart is unquestionably with Aristotle, as he makes clear in his broad praise for Rand’s aversion to Platonism and also in his description of Hayek at the end of his life watching televised images of the overthrow of Communism in Czechoslovakia in 1989. “I told you so,” Hayek tells his son, to which Herman adds, “So had Aristotle.” Given his political views, this Aristotelianism should come as no surprise. “Today’s affluent, globalized material world,” Herman writes, “was largely made by Aristotle’s offspring.” But while he not only greatly prefers Aristotle, but also taxes Plato’s intellectual and spiritual heirs with virtually every political tendency and historical development in European and global history that he deplores, Herman nevertheless insists that “our world still needs its Plato.”

In Hayek’s terms, and—to careen vertiginously down the intellectual and moral food chain—in Rand’s as well, such a view is anathema. Late in The Cave and the Light, Herman approvingly quotes Rand’s assertion that “everything that makes us civilized beings, every rational value that we possess—including the birth of science, the industrial revolution, the creation of America, even the [logical] structure of our language, is the result of Aristotle’s influence.” Hayek’s view was far more nuanced (but then, compared with Rand’s, whose wasn’t?), and he was less concerned with praising Aristotle than with rejecting Platonism. For as his denunciations of solidarity and altruism in his book The Fatal Conceit make clear, Hayek viewed Platonism as a kind of owner’s manual for totalitarianism and saw socialism as Platonism’s twentieth-century avatar, much in the same way that Karl Popper did. But unlike his intellectual heroes, Herman insists on Western society’s need for Platonism as well as Aristotelianism. Though he returns over and over to Platonism’s intrinsic faults, and, by extension, to its economic fatuities and the world-historical crimes to which it has given rise, from Bolshevism and the Gulag to what Herman calls Plato’s “American offspring”—a term capacious enough to include Josiah Royce, John Dewey, Woodrow Wilson and FDR—Herman is adamant that Platonism remains key to the West’s identity, and a necessary corrective to Aristotelian dynamism, with its constant, stupefying potential for change.

This may seem contradictory (it certainly would have to Hayek and Rand, and surely cannot sit well with many of Herman’s colleagues at the AEI), but in fact it constitutes the core of Herman’s thesis. For him, it is the “tension” between the West’s Platonic “spiritual self” and its Aristotelian “material self” that has allowed the West to continue its “never-ending ever-ascending circle of renewal.”

For so proudly an anti-Hegelian, anti-Marxist writer as Herman, this tension he deems so essential bears a surprisingly close resemblance to G. W. F. Hegel’s idea, later taken up by Karl Marx and his twentieth-century inheritors, of the dialectic—that is, of thesis and antithesis that sooner or later are combined in a synthesis that represents either a compromise between the two initial philosophical or moral positions, or a combination of the best features of each. To be sure, Herman’s version of the dialectic is one that puts more emphasis on the creative tension between the two philosophical stances and less on the possibility of any enduring compromise or synthesis between them. As Herman puts it, while discussing what he argues was the English romantics’ doomed effort to reconcile the Platonic and the Aristotelian, “The creative drive of Western civilization had arisen not from a reconciliation of the two halves but from a constant alert tension between them.”

But Herman is inconsistent on this point. For example, in the concluding paragraphs of his book he asserts that this tension “inspired one breakthrough after another” in the clash between Christianity and classical culture, in what he anachronistically calls the “culture wars” between the romantics and the Enlightenment, and today, in the clash “over Darwinism and creationism or ‘intelligent design.’” He is explicitly making a case for what he calls the “indispensability” of both the Platonic and the Aristotelian worldviews in the creation of the Western synthesis that the “all-pervasive tug of war” between those worldviews has produced over the centuries. That tension and renewal, he argues, “are our [Western] identity.”

TO A HAMMER, everything is a nail. No one would deny that, in the Western tradition at least, the Greeks “invented” politics. But to go from this to saying that one can understand all the major political events in Western history as somehow being expressions of the spirit of Plato or Aristotle or of some tension between the two schools of thought as refracted down through the centuries really does stretch credulity. In fairness, such vast oversimplifications have always been the stuff of popular history, and popular history certainly has its place. If, for example, one wanted to recommend a book to an intellectually ambitious but not particularly well-read high-school sophomore, one could do a lot worse than Herman’s conspectus. It moves along jauntily, and its explanations, wild oversimplifications though they generally are, provide a basic framework for the future studies that, if undertaken and supervised properly, will challenge and overturn most of Herman’s facile binary summations. Herman himself points to this approach when he rather startlingly declares in his book’s concluding passage that the intellectual and moral tug-of-war dating back to classical times between Plato and Aristotle could also be called “yin and yang or right brain versus left brain.”

TO A HAMMER, everything is a nail. No one would deny that, in the Western tradition at least, the Greeks “invented” politics. But to go from this to saying that one can understand all the major political events in Western history as somehow being expressions of the spirit of Plato or Aristotle or of some tension between the two schools of thought as refracted down through the centuries really does stretch credulity. In fairness, such vast oversimplifications have always been the stuff of popular history, and popular history certainly has its place. If, for example, one wanted to recommend a book to an intellectually ambitious but not particularly well-read high-school sophomore, one could do a lot worse than Herman’s conspectus. It moves along jauntily, and its explanations, wild oversimplifications though they generally are, provide a basic framework for the future studies that, if undertaken and supervised properly, will challenge and overturn most of Herman’s facile binary summations. Herman himself points to this approach when he rather startlingly declares in his book’s concluding passage that the intellectual and moral tug-of-war dating back to classical times between Plato and Aristotle could also be called “yin and yang or right brain versus left brain.”

In doing this, Herman in effect vitiates his own most fundamental claims. There is no point in assaying a vast work of intellectual history if all one is actually doing is saying that in all cultures and, arguably, in all human beings, there is a tension between the rational and the irrational, the spiritual and the material, or the scientific and the artistic. Any of a thousand self-help books published over the last three decades can tell you that. And yet, reduced to its bare essentials, this is precisely what Herman ends up doing. According to him, “It is the balance between living in the material and adhering to the spiritual that sustains any society’s cultural health.” This seems more appropriate to a New Age retreat than to a believer in a very different, and in many ways far more mystical construct—a West that will never decline or be superseded because of that “never-ending ever-renewing circle of renewal” Herman invokes as if it were an undeniable fact rather than the hubristic, ahistorical fantasy that it actually is. It also raises the more interesting question of whether The Cave and the Light can properly be called a work of history at all.

To be clear, while the book begins and ends philosophically, its core is a straightforward work of intellectual history in which each major paradigm shift within the Western tradition, whether religious or secular, is described as being the expression in history of either the Platonic or the Aristotelian tradition or of some synthesis of the two. Thus, what Machiavelli “did in reality was to plug Aristotle’s formula for understanding civic liberty into Polybius’s time machine, the inevitable cycle of historical rise and decline.” To cite another example, Herman quotes Percy Bysshe Shelley’s celebrated if floridly narcissistic line about poets being “the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” According to Herman, what Shelley actually meant was that poets were “Plato’s Philosopher Rulers in the flesh, for a world desperately needing the emanations of their genius”—a claim about which the fine old Scottish legal verdict, with which Herman, given all the hagiographical things he has said of the Scots, is surely aware, would seem to be the most generous response one can make: not proven. But to describe historical events is not the same thing as being a historian in any true sense of the word, just as writing sweepingly on a broad range of subjects does not make you a polymath.

THE PROBLEM with The Cave and the Light is not Herman’s unfortunate tendency to ignore the sensible adage, usually attributed to Mies van der Rohe, that sometimes less is more, and instead to provide utterly baseless “color” and novelistic details about the historical figures he is describing—grating as these often are. Examples of these abound, even if, for example, Herman cannot possibly know whether, as Michelangelo walked from his lodgings to the Vatican Palace in 1510 to work on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling, whether Bramante’s workmen “appeared like shadows, as they yawned and stretched among the piles of masonry and coils of rope” in front of the unfinished basilica of St. Peter’s. Nor can Herman have the remotest idea as to whether Gerard of Cremona, who would go on to translate Aristotle’s On the Heavens into Latin, thus reintroducing him to the Western world, reacted to the Muslim call to prayer by thinking that it seemed “like an audial illusion, like the cry of a bird that you briefly mistake for a human voice” when he visited Toledo in 1140. And these are only two of many examples of such poorly grounded speculation.

A more serious defect is that Herman is an extraordinarily old-fashioned writer (not, to avoid misunderstanding, because he is a man of the political Right: so is John Lukacs and his work suffers from no such infirmity), and an even more defiantly retrograde thinker. Herman’s practice as a historian is a throwback to what nineteenth-century German academics called Geistesgeschichte—that is, history conceived of almost exclusively as the identification and description of the “spirit” of the times. It is actually almost refreshing, if not very serious, to read a work from which material history as practiced by such great historians as Fernand Braudel and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie—the history of climate, of agriculture, of migration—is so singularly absent and in which great men and great (or terrible) ideas all but exclusively determine the course of events. At times, Herman can be quite shameless about this, as when, in his chapter describing the rise of Christianity in the Roman world, he blandly opines that “today, historians point to social and economic factors to explain Christianity’s amazing spread. But the key factor was its skill in seizing the high ground of Greek thought, especially Plato.”

To call this an impoverished and partial account not only of Christianity’s encounter with the classical world but also of Western civilization more broadly is about the kindest possible way to put the matter. This can seem almost poignant given that his general tone—and at least some of the way he chose to frame his thoughts—suggests that Herman’s purpose was to defend the West against its detractors both at home and abroad. But by insisting that everything that has happened in the West since Aristotle’s death is in one form or another indebted to the legacy left by him and by Plato, Herman does the tradition he is so determined to uphold no favors. Quite the contrary. Herman’s own discipline, history, owes everything to the Greeks but little or nothing to Plato or Aristotle. As the great Oxford classicist Sir Moses Finley pointed out in his 1965 essay, “Myth, Memory and History,” Aristotle, though he “founded a number of sciences and made all the others his own, too, in one fashion or another. . . . did not jibe at history, he rejected it.” Finley goes on to quote the passage in the ninth chapter of the Poetics in which Aristotle says, “Poetry is more philosophical and more weighty than history, for poetry speaks rather of the universal, history of the particular.” Both Plato himself and the Neoplatonists were even more dismissive. And, again, as his remark about the eternal renewal of the West suggests, it is hard not to feel that, almost in defiance of his own vocation, Herman shares this view to an uncomfortable, not to say embarrassing, extent.

A SECOND DIFFICULTY with the book is its woefully superficial and—if not wholly in tone then certainly in substance—dismissive treatment of the centrality of Judaism in the formation of Western culture and politics. In Herman’s account, it was Plato whose works “provided a framework for making Christianity intellectually respectable [in the classical world], while Christianity in turn gave Plato’s philosophy a shining new relevance.” There is no doubt that the history of its interaction with classical culture is central to the early church—even if Herman is at his vulgar worst when, apparently in all seriousness, he observes that the “forerunners of the stereotypical nuns with steel rulers are Plato’s Guardians in the Republic.” Herman does devote some passages to the Alexandrian Jewish philosopher, Philo. But, to appropriate the title of one of Leo Strauss’s most important books, Athens is omnipresent but Jerusalem all but absent from Herman’s account of Christianity’s rise, even though, as Strauss wrote, “The Platonic statement taken in conjunction with the biblical statement brings out the fundamental opposition of Athens at its peak to Jerusalem: the opposition of the God or gods of the philosophers to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the opposition of reason and revelation.”

This is a grave and telling error both historically and philosophically. Instead of a polarity between Plato and Aristotle, Strauss posed what the great French political philosopher, Pierre Manent, has correctly characterized as a different polarity. Plato and Aristotle (not Plato or Aristotle) are on one side of this dichotomy, but it is Judaism and not philosophy that is on the other. Herman discusses St. Augustine in considerable detail, but what he focuses on is what he calls Augustine’s “final authoritative fusion of Neoplatonism and Christianity,” which would “have a sweeping impact on Western culture for the next thousand years and beyond,” even if, four hundred years later, in what even for Herman is a crass low stylistically, Aristotle would “strike back.” Manent’s version is rather different. For him, Augustine co-opted Plato for his own purposes, rather than, as it so often seems reading Herman, being co-opted by him. Anyone tempted by Herman’s reductive account would be well advised to read Manent’s entire essay, which appeared in First Things in 2012. In it, he wrote:

For Augustine, Christianity confirms these two separations while overcoming them. He presents Christianity as the resolution of the two decisive breaks of human unity: the Jewish and the Greek. The mediation of the God-man Christ allows the unity of mankind to be restored while each human being is made capable of sharing in the truth enacted by Jewish life as well as the truth discovered by Greek philosophy. Jewish life and Greek philosophy, two very different ways of finding one’s way toward the true God, prepared humanity for the decisive step only God could take.

We are a long way from Herman’s dire simplicities about how Augustine’s City of God represents “a kind of Platonic ideal.” As Thorleif Boman pointed out more than half a century ago in his magisterial study, Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek, the Jews of the Roman Empire of that period “defined their spiritual pre-disposition as anti-Hellenic.” To be sure, had the early Christians chosen to expunge all traces of their faith’s Jewish roots, Herman’s account of what he calls the “thoroughgoing synthesis between Christian revelation and ancient reason, between Plato and Jesus” would be dispositive. It was this that the second-century bishop Marcion had pressed for, proposing an alternate canon beginning with an expurgated version of the Gospel of Luke and the ten Epistles of Paul. But the Marcionite project that opposed the God of the Old Testament to Jesus as revealed in the New Testament failed, and with it so did the attempt, as the English Biblical scholar Sydney Herbert Mellone once put it, to propose the advent of Jesus as “an entirely new event, with no roots in the past history of the Jewish people or of the human race.” One can fairly assert that historically relations between institutional Christianity and the Jewish people have been nothing short of catastrophic. But this does not mean that, to cite Boman again, “the question of the formal and real relationship between Israelite-Jewish and Greek-Hellenistic thinking” was any less of a “live problem” for Christianity and the church, as one might infer from the scant attention Herman pays to the role of Hebrew thought in the shaping of Christian dogma and the formation of the Christian commonwealth. And even if one views Augustine largely as a Christianized Neoplatonist, as Herman apparently does, the relevant tension, to use Herman’s preferred term, is not between Augustine’s Neoplatonism and some Aristotelian alternative, but between that Neoplatonism and the Jewish tradition out of which Christianity had come.

But perhaps the most curious aspect of The Cave and the Light is the way in which Herman seems to want to downplay the Western tradition as fundamentally Christian. If, as Herman claims, the influence of Plato and Aristotle down through the centuries was “the greatest intellectual and cultural journey in history,” then in a sense he is forced to write from the perspective of Christianity being only one stop, however long and important, on that trip. It is not only the obvious fact that neither Plato nor Aristotle was Christian. After all, Augustine or Aquinas could be adduced to deal with that. Rather, it is the fact that Herman’s depiction of our own times is almost ostentatiously post-Christian. He does emphasize the spiritual needs to which Platonism and its heirs seem to be able to respond while Aristotelianism cannot. But this spirituality has no specific content, and certainly no particularly Christian content. Indeed, near the end of his book, Herman speaks not of Jesus Christ dying for the sins of humankind, but instead avers that all of Western history can be summed up as “a battle founded, in the last analysis, on the irreconcilable contradiction between Plato’s God and Aristotle’s Prime Mover.”

Given all the historical elements this analysis forces Herman to downplay or at times ignore, this claim seems much more far-fetched than the traditional understanding, well articulated in the modern era by Pope John Paul II, of Western civilization as a fundamentally Christian construct, to which, unquestionably, the thought of both Plato and Aristotle made important contributions. But then, Herman does appear to have an awfully pagan understanding of Western identity. When he writes that “tension and renewal are our [Western] identity,” he begins to sound more like a member of some mystery cult of the Roman era—Mithraism comes to mind, though there were others—than either a Greek philosopher or a Christian. And why he thinks that rediscovering that identity might allow the West to “save the world” is not the smallest puzzle of this comically pretentious excursus into the past.

David Rieff is the author of eight books, including A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis (Simon & Schuster, 2003) and At the Point of a Gun: Democratic Dreams and Armed Intervention (Simon & Schuster, 2005).

Pullquote: To say that one can understand all the major political events in Western history as somehow being expressions of the spirit of Plato or Aristotle really does stretch credulity.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review