Obama and the War Decision

History teaches that failed wars destroy presidencies. As the debate over whether to strike Iran heats up, the current commander-in-chief should heed this lesson.

Talk of war is in the air. And as tensions mount between the United States and Iran, it’s proper to assess the lessons of history as they relate to presidential war decisions. The first is that American presidents face no decision more politically dangerous than the choice to take the country into armed hostilities. It can bring glory to the White House occupant, but it can just as easily bring ignominy. Consider the presidencies of Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson. All saw their political standing plummet amid war outcomes far different from what had been anticipated in the flush of excitement at war’s beginning. The same happened to George W. Bush, who managed to get through his 2004 reelection effort despite growing difficulties in Iraq. Four years later, however, the full extent of the Iraq mess was evident, and that contributed to the double whammy that befell Republicans in the 2006 and 2008 elections.

Talk of war is in the air. And as tensions mount between the United States and Iran, it’s proper to assess the lessons of history as they relate to presidential war decisions. The first is that American presidents face no decision more politically dangerous than the choice to take the country into armed hostilities. It can bring glory to the White House occupant, but it can just as easily bring ignominy. Consider the presidencies of Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson. All saw their political standing plummet amid war outcomes far different from what had been anticipated in the flush of excitement at war’s beginning. The same happened to George W. Bush, who managed to get through his 2004 reelection effort despite growing difficulties in Iraq. Four years later, however, the full extent of the Iraq mess was evident, and that contributed to the double whammy that befell Republicans in the 2006 and 2008 elections.

Even Abraham Lincoln, generally considered by historians to be the greatest president, nearly came a cropper due to the carnage of war he had unleashed and which, right up until the fall of 1864, still looked like a hopeless stalemate. In fact, just six weeks before the election Lincoln wrote a note to himself, to be stuffed into a drawer until after the balloting. He wrote: “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so cooperate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards.”

Between the writing of that note and the election, three military developments occurred: General William Sherman took Atlanta; General Philip Sheridan gained military dominance over the Shenandoah Valley, a key Confederate supply source; and the last Confederate ramming vessel, the Albemarle, was sunk in the Roanoke River, ending rebel resistance to the Union’s naval blockade of the South. These military victories in the field favorably altered the political landscape at home, and Lincoln’s electoral standing soared. Such are the vagaries of war as applied to American politics.

Another lesson might be called the Polk-Johnson-Bush lesson: ensure that no one can ever make an accusation that the president dissembled to the American people in order to get permission to spill American blood. Polk sent an army into disputed territory between Mexico and the newly acquired Texas, and when a skirmish inevitably broke out he declared that the Mexicans had “spilled American blood upon the American soil.” This later came to haunt him as the war lingered on far longer than Polk or America had anticipated or wanted. Johnson’s pronouncements surrounding the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 were flung at him with devastating effect as his war in Vietnam dragged on. We all know the Bush story—weapons of mass destruction that never materialized and presumed Iraqi ties to terrorist groups that were never proven. Thus Bush crafted a rationale for war that was either disingenuous or carelessly flimsy (I believe the latter).

Another lesson: don’t get bogged down in a war you can’t win and can’t end. That was Truman’s fate in Korea and Johnson’s in Vietnam. Those wars sapped the political standing of both to such an extent that neither could seriously entertain a bid for reelection. Leaving aside economic calamities, nothing turns the electorate against an incumbent president with as much force as does such a negative wartime development. Even if prospects for victory remain, this becomes irrelevant once the American people conclude such prospects no longer are worth the effort. Then the man in the White House comes under fearsome political pressure.

Finally, it becomes almost impossible for any president to control events once the shooting starts. Polk is a good example. He never wanted a protracted war, but he got one. He never wished to conquer Mexican territory he didn’t want to acquire for America, but he was forced into doing so as the proud Mexicans refused to treat for peace even as they suffered consistent military humiliation in the field. He never anticipated that his military command would disintegrate, with various top generals facing courts-martial, but that happened on his watch. During his two-year Mexican War, Polk couldn’t control events; instead, events constantly thrust him onto the defensive.

When it comes to domestic policy, particularly economic policy, the voters watch their presidents closely. Anything related to jobs and their plentitude, or their diminution, is monitored on an ongoing basis. But on foreign policy the voters are more inclined to delegate decision making to their chief executives—who, it is assumed, understand the complexities of the world far better than the voters. Even when the commander in chief attempts to lead the nation to war, the electorate generally accepts that judgment and rallies to the cause.

But this delegation of authority comes with a powerful proviso: don’t mess it up. When it comes to the expenditure of blood, the American people expect the rationale of war to hold up; they expect honesty in that rationale; they expect a benefit to the nation from the sacrifices involved; they expect effectiveness in the war effort; and they demand victory within a reasonable time span. When those things aren’t in evidence, the voters terminate their delegation of authority and force a policy change—sometimes effected through a change in personnel—at the next election.

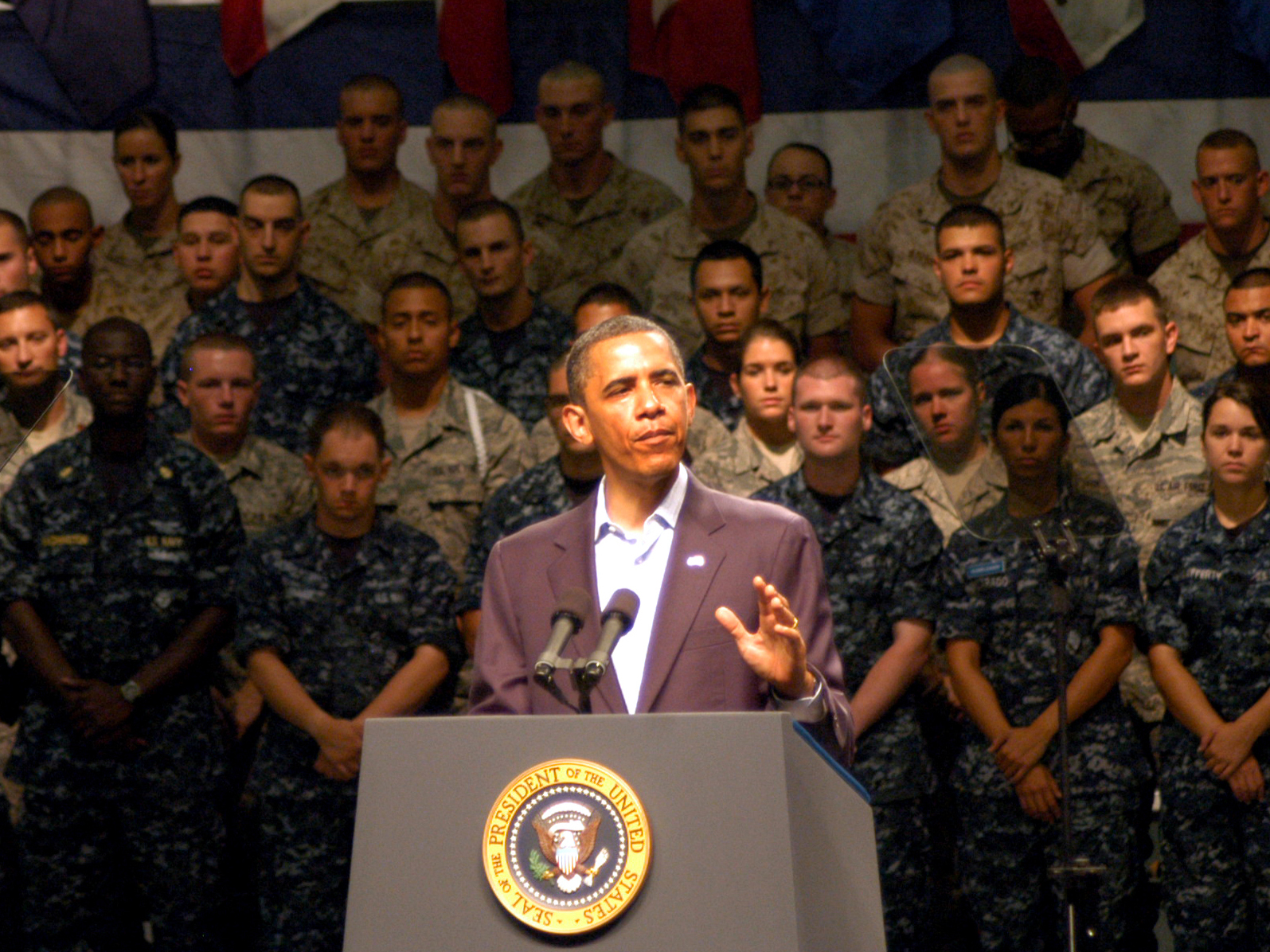

These realities should be on the mind of President Obama as tensions between the United States and Iran intensify and as Israel seems increasingly bent on forcing America into a war with the Islamic Republic. The recent example of George W. Bush is instructive. The historical picture of his administration that has emerged thus far indicates strongly that he and his advisers never really contemplated all the complexities and eventualities that would converge upon them once he issued his order to invade Iraq. The result was that neither he nor the American people were prepared for the events unleashed by that presidential decision.

That’s a politically dangerous situation for any president, as the fate of Republicans in the 2006 and 2008 elections makes clear. President Obama would do well to contemplate in exhaustive detail all of history’s lessons of presidential war making before he renders a decision to lead America into another Mideast conflict.

Robert W. Merry is editor of The National Interest and the author of books on American history and foreign policy.