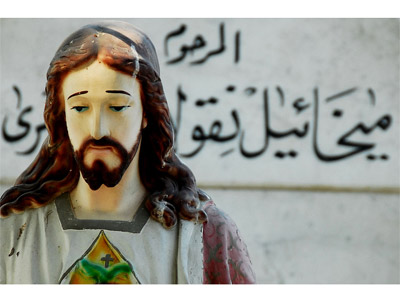

The Crushing of Middle Eastern Christianity

Popular uprisings, social transformations and American interventions have hurt the region's second-largest religion.

Americans of all political stripes have embraced the promotion of democracy as a centerpiece of U.S. foreign policy. But this American democracy crusade has caused huge, and largely overlooked, collateral damage since the 9/11 Al Qaeda attacks against the United States in 2001. The fall of authoritarian regimes throughout the greater Middle East has fueled growing persecution of minority Christian communities. The Pew Research Center has charted extensive government restrictions on non-Muslim religions in numerous countries, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Iran, Tunisia, Syria, Yemen and Algeria. Pew also has gauged very high social hostilities in Pakistan, Iraq, Yemen, the Palestinian territories, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Americans of all political stripes have embraced the promotion of democracy as a centerpiece of U.S. foreign policy. But this American democracy crusade has caused huge, and largely overlooked, collateral damage since the 9/11 Al Qaeda attacks against the United States in 2001. The fall of authoritarian regimes throughout the greater Middle East has fueled growing persecution of minority Christian communities. The Pew Research Center has charted extensive government restrictions on non-Muslim religions in numerous countries, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Iran, Tunisia, Syria, Yemen and Algeria. Pew also has gauged very high social hostilities in Pakistan, Iraq, Yemen, the Palestinian territories, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

These government restrictions and social hostilities directed against Christians are causing many to flee the region. In the early twentieth century, Christians accounted for about 20 percent of the Middle East population, but now that figure is down to only 5 percent. In the aftermath of 9/11 and the “Arab Spring,” Christian communities throughout the greater Middle East find themselves increasingly besieged. While the United States seems to notice bits and pieces of this picture, the full magnitude of the horrific Christian plight is largely ignored.

Sieges against Christians in Lands “Liberated” by the American Military

A democracy enthusiast would anticipate that the Christian community would be thriving now that a “democratic” Afghan government was installed by American military power after the ouster in 2001 of the Taliban regime. After all, Afghanistan’s constitution, adopted in 2004, guarantees freedom of religion. But Afghan Christians today are compelled to worship in secret lest they be accused of apostasy for converting to Christianity from Islam, a charge punishable by death. Such persecution no doubt will grow after 2014, when American soldiers are largely gone and Washington is less able to influence the government in Kabul.

Across a troublesome border, Pakistan’s blasphemy laws are wielded more and more aggressively against Christians by a weak civilian government propped up by Pakistan’s Islamized military and society. Christians, who make up only about 2 percent of Pakistan’s 180 million people, are living under growing fear of persecution and economic discrimination. The assassination in March 2011 of the only Christian minister in Pakistan, who bravely criticized harsh blasphemy laws that impose the death penalty for insulting Islam, has chilled the willingness of secular and liberal Pakistanis to speak out.

Iraq’s open warfare against its Christian community has led to a mass exodus of Christians from that country since the 2003 American and British military invasion ousted Saddam Hussein, whose repugnant regime was nevertheless relatively hospitable to Christians. Iraqi Christians are severely embattled by Sunni extremists linked to Al Qaeda and are discriminated against by Iraq’s Shia majority, largely in control of the government. Incidents such as the 2010 suicide bombing of Our Lady of Salvation Church in Baghdad, which killed fifty Christians and two priests, have terrified Iraq’s Christian population, which has dwindled to less than 500,000 from between 800,000 and 1.4 million in the time of Saddam.

Sieges against Christians in Lands Coping with the Arab Spring

The current Egyptian regime, dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood, poses a far greater threat to Egypt’s sizable Coptic Christian community than its authoritarian predecessor under Hosni Mubarak. A Coptic church in Cairo was set ablaze by Islamists in 2011 and many Copts—an estimated 10 percent of Egypt’s 85 million people—live in fear that Egypt is on the path to being governed by Islamic law, or Sharia. In early April 2013, Egypt’s police sided with an angry crowd of young Muslims throwing rocks and firebombs in a siege of Egypt’s major Coptic Cathedral. Nor have Egyptian Copts, who have sought work in neighboring Libya, fared well in the chaos that has reined in that country since the fall of Muammar Gaddafi. Christians were shocked in December 2012 by the bombing of a church in Misrata, Libya. That attack has stoked fears that Libyan Islamists are growing in power and more such attacks against Christians are in store.

Islamists also are emerging as a powerful force in Syria, generating fears that, should they gain power, they would persecute Syria’s Christian community. About three hundred thousand Christian Syrians have already fled the country and are refugees. A Christian patriarch in April 2013 warned, “The future of Christians in Syria is threatened not by Muslims but by…chaos…and the infiltration of uncontrollable fanatical fundamentalist groups.”

Now Syria’s violence is spilling over into neighboring Lebanon. The Shia Islamist group Hezbollah is flexing its military muscles and lending support to embattled Syrian forces. Many Lebanese Christians have fled over the years due to civil war and, more recently, in fear that Hezbollah eventually will control the country and turn it into an Islamic state. Christians made up about fifty percent of the country in 1932, during the last national census, but now by some estimates are only 34 percent of the population. A similar trend has long been under way in the Christian Palestinian community, caught in the middle of the conflict between the Israelis on one side and secular and Islamist Palestinians on the other. The Catholic Patriarch of Jerusalem has lamented that the Holy Land is fast becoming a “spiritual Disneyland,” with holy sites as theme park attractions bereft of worshipping Christians.

In the small, rich Arab Gulf states, Christian communities, formed primarily by Asian immigrate workers, quietly practice their faith, but that isn’t happening in the region’s powerhouse Saudi Arabia. Qatar, for example, has allowed the construction of a Catholic church in Doha for one hundred and fifty thousand Catholics. Churches in Kuwait, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates are seen as a way to lure expatriate labor to those countries. These Gulf States have survived the political torrents of the Arab spring, but should they fall to street protests, successor regimes likely would resemble Saudi Arabia today, which forbids Christian worship by the estimated eight hundred thousand Catholics in the kingdom. The Saudi government publicly lauds interfaith dialogue, but Saudi-sponsored conferences take place outside the kingdom to avoid domestic religious-political backlashes from Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi religious establishment.

Sieges against Christians in Non-Arab Middle East Lands

The tightening sieges of Christian communities in the Arab Middle East is running parallel to sieges laid against Christian communities by non-Arab Muslims elsewhere in the region. The Assyrian Christian population in Iran has plummeted from about one hundred thousand in the mid-1970s to about fifteen thousand today. More than three hundred Christians have been arrested by Iran’s Islamic regime since mid-2010. Churches operate in fear. And Christian converts face persecution. Meanwhile, Turkey is praised in the West as a democratic success story in the Muslim world, and the government in Ankara often is characterized in the media as “mildly Islamic.” But the steady erosion of free-speech rights in Turkey, as evidenced by the increasing imprisonment of journalists and the government’s aggressive purging of the secular Turkish military, raises doubts about the future prospects for Turkish political and religious tolerance. Attacks against Christian leaders in Turkey have raised concerns about the security of roughly one hundred thousand Christians living in a country of 71 million Muslims. A Catholic bishop was stabbed to death in southern Turkey in 2010, and several years earlier a Catholic priest was murdered in a Turkish town along the Black Sea.

Demand for Blunt American Talk and Diplomacy

Democracies consist of more than just elections. They must also have divided powers among executive, legislative and judicial branches, as well as protected practices of freedom of expression and religious belief. The mistreatment of Christian communities throughout the Muslim Middle East powerfully undermines any assertion that Islamic societies are tolerant of other faiths, and will continue to rebuke such assertions so long as the regimes and societies writ large fail to protect Christian minorities with words and deeds.

The United States cannot be the world’s policeman in behalf of democracy and religious tolerance. The horrendous loss of our national treasure, both in fallen soldiers and enormous costs, vividly and painfully reminds Americans that we lack the power, means and interests to militarily intervene wherever there is human tragedy. Nevertheless, Americans ought to recognize that the “soft power” of rhetoric and diplomacy can influence world events at the margins. Regimes in the greater Middle East, like nation-states everywhere, want power and prestige in international relations, and they can be “shamed” in the eyes of world opinion. Washington should seek to embarrass governments and pressure them to lift the sieges of Christians that are now so prevalent throughout the Middle East. Then we would see whether they truly aspire to be called, and treated as, genuine democracies.

Richard L. Russell is Professor of National Security Affairs at the Near East and South Asia Center for Strategic Studies. He is the author of Sharpening Strategic Intelligence, Weapons Proliferation and War in the Greater Middle East, and George F. Kennan’s Strategic Thought. The views expressed are those of the author alone.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Tinou Bao. CC BY 2.0.