Is a Thaw in U.S.-China Relations Possible?

The less short-term urgency Beijing feels to achieve reunification, the more time Washington will have to hone a blend of deterrence and reassurance that reduces the odds of a catastrophic confrontation.

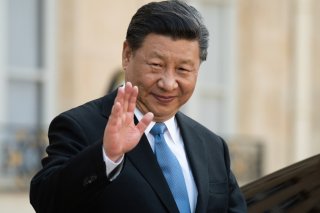

Last month’s meeting between U.S. President Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping in San Francisco—the culmination of months of diplomacy between high-level U.S. and Chinese officials—will likely contribute to stabilizing relations between Washington and Beijing, at least over the short term. The two leaders agreed to establish several channels to enhance military-to-military cooperation, cooperate to stem the flow of fentanyl precursors from China, and expand two-way direct flights and other forms of people-to-people exchange.

But such outcomes cannot be expected to change the fundamentally competitive nature of the U.S.-China relationship. Indeed, that competition is poised to intensify across geographies and functions. And U.S.-China diplomacy remains fragile; in February, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken canceled his planned visit to China amid the Biden administration’s detection of a suspected Chinese spy balloon near a military base in Montana.

The good news, though, is that both President Biden and President Xi have strong short-term incentives to put a floor under the U.S.-China relationship. Biden, grappling with a grisly war between Russia and Ukraine and an escalating crisis between Israel and Hamas, can ill afford to contend with a third theater of crisis. Xi, meanwhile, is confronting mounting economic headwinds at home and an increasingly adversarial relationship with the world’s advanced industrial democracies.

Still, a major test of the relationship is quickly approaching: Taiwan will elect a new president on January 13, with William Lai Ching-te of the Democratic Progressive Party favored to win. Lai, who calls himself a “Taiwan independence worker,” could take steps to erode the cross-Strait status quo, potentially with significant support from the U.S. Congress. And Beijing continues to intensify its coercion of Taipei. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) launched ballistic missiles over Taiwan during a visit to the island last August by former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi—the first time it had done so since the 1995-96 Taiwan Strait Crisis.

And yet, there are at least three reasons to believe that Beijing is not seriously considering an invasion for now. First, as Jude Blanchette and Bonnie Glaser explain, it still has ample room to pursue a patient, multifaceted “strangulation” effort—that is, “an increasingly aggressive ‘gray zone’ campaign of political, psychological, economic, and diplomatic coercion that is designed to make Taiwan’s citizens feel powerless, divided, and isolated.” Barring a highly unexpected precipitant—say, a decision by Taiwan’s next president to declare the island’s independence or a formal U.S. renunciation of “strategic ambiguity”—China is unlikely to choose a high-risk gambit for which the PLA is manifestly unprepared. Second, a failed invasion attempt, with the enormous military, economic, and diplomatic costs that it would entail, would arguably do more to jeopardize Xi’s quest for “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” than any other development. Third, while Xi appreciates that China’s strategic outlook is more challenged than it was at the outset of the decade, there is little, if any, evidence to suggest that his long-term assessment of its role in world affairs is dimming. Whether China’s comprehensive national power is nearing its zenith matters less than whether he believes it to be so.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also furnishes a cautionary tale for China. While Ukraine’s counteroffensive may be faltering, Putin has fallen far short of achieving not only his original objective—conquering the whole of the country—but even the minimal objective of retaking formerly Russian-occupied territories that are now under Kyiv’s control. Brain drain and tightening Western sanctions threaten Russia’s medium- to long-term growth prospects, huge materiel losses and a decreasing capacity to procure semiconductors undercut its defense industrial base, and a revitalized transatlantic alliance and Indian apprehension over deepening Sino-Russian ties limit its diplomatic heft. In short, Russia’s geopolitical outlook stands significantly diminished.

One cannot rule out that, even with the benefit of hindsight, Putin may still have authorized Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But Russia, as a stagnating power that cannot credibly hope to become a peer competitor to the United States, has far less to lose from undertaking destabilizing actions—up to and including the full-fledged invasion of a sovereign country—than China, a resurgent power that could plausibly become one on the back of its economic heft and innovative capacity.

What lessons might Xi be learning from Russia’s difficulties in Ukraine? At least three come to mind. First, even if an aggressor possesses overwhelming superiority in conventional military terms, it can stumble if its leadership underestimates its opponent’s will to fight. While Xi has instructed the PLA to have the capacity to invade Taiwan by 2027, the turbulence among its top echelons suggests that he may lack confidence in its preparedness, especially given that China’s operational challenge—to stage an amphibious landing—would be vastly more complicated than conducting a ground invasion of a territorially contiguous neighbor. Second, in no small part owing to the first reason, the hope of a “short war” against Taiwan is increasingly chimerical. Few observers likely imagined on February 24, 2022, that Ukraine would still be holding its own against Russia nearly two years later. Taiwan is building formidable “porcupine defenses” to deter Chinese aggression, and its mountainous terrain would present enormous operational challenges for the PLA. Third, China’s comprehensive integration into the world economy makes it more vulnerable to economic punishment than Russia; in particular, its significant dependence on Western microprocessing chips would limit its ability to blunt a coordinated decoupling effort by advanced industrial democracies.

Paradoxically, then, even as the United States works to dissuade a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, it should affirm China’s optimism about the future: the less short-term urgency Beijing feels to achieve reunification, the more time Washington will have to hone a blend of deterrence and reassurance that reduces the odds of a catastrophic confrontation.

Ali Wyne is the author of America’s Great-Power Opportunity: Revitalizing U.S. Foreign Policy to Meet the Challenges of Strategic Competition (2022).

David Gordon is a senior advisor at Eurasia Group and a former director of policy planning at the State Department.

Image: Shutterstock.com.