The Real Thucydides Trap: Will Red and Blue America Go to War?

Thucydides warns us to not discount the possibility of war between red and blue states.

In the aftermath of the 2016 elections, an intense and widening divide resurfaced among Americans. While initial fissures in U.S. society revealed themselves over twenty years ago, the split increased into culturally distinct and regionally localized areas during that time. Today, the rift is generally peaceful and manifests itself in words and demonstrations. However, it resides along significant geographic, economic and ideological lines that may not withstand future stress and pressure.

Such an internal division is not a unique circumstance. In fact, ancient Greek history provides us a fitting analogy for reflection. Senior military leaders and historians study The Peloponnesian War, written by the Athenian historian Thucydides, as a footnote for strategic thought in foreign affairs. However, that war was chiefly about internal conflict in Greek society. Today, Thucydides’ relevance to America’s domestic political landscape is minimal under an assumption the United States is a unified society. Clearly, the 2016 elections and reactions give cause to question the strength and depth of our society’s unity. That and other similarities warrant a review of the context and causes of the Peloponnesian War, if only as an analogy, for consideration.

The thirty-year-long Peloponnesian War did not start overnight. Greek casus belli intensified gradually over a fifty-year span as selfish agendas became acceptable through the slow creep of greed, pride and suspicion. Ironically, the very peace Athenians and Spartans secured against Persia enabled the widening of attitudes. Tragically, Greek divergence metastasized into open conflict and, ultimately, mutual ruin.

Why? A key message of Thucydidean history is that without mutual effort for unity, a people of common heritage but different perspectives will develop oppositional interests over time. This was the case with Athens and Sparta and is occurring in “blue” and “red” segments of America’s populace.

From a geographical perspective, America’s socio-political affiliations coalesce in distinctive regions such as urban areas next to oceans and rural heartlands. While geography does not predetermine societal destiny, it is a feature that influences its culture and end results. Although separated by era and ocean, the geographic and societal disposition of today’s “blue” and “red” American states have stark similarities to that of Athens and Sparta.

As example, in 450 BC, Athens resided within a great walled city with access to the Aegean Sea. Facing seaward, it used its powerful navy to spur trade and enlarge its influence abroad bringing it into cooperation with other cultures. Similar to America’s “blue” populations on the Pacific and northeastern Atlantic coasts and in major metropolitan centers, Athens was mercantile, inclusive, cosmopolitan and urbane. As with Athens, “blue” populations view themselves as exemplars and vanguards for Western civilization’s progress at home and abroad.

Athens’ rival was Sparta, principally an agrarian society husbanded within the countryside and without continual contact with overseas cultures. Sparta maintained a formidable army and militant ethos to protect its land’s resources against enemies. Comparably, “red” states dominate the American heartland where its populations view foreigners with skepticism and espouse greater comfort with the Second Amendment. Sparta subjugated a Helot slave population allowing only native Spartiates to govern. Regrettably, a similar legacy still exists in “red” southern states. Rustic, trusting religious oracles, and zealous when threatened, Sparta and “red” states regard tradition and military might as touchstones to national prestige.

For Athens and Sparta, as in “blue” and “red” states, their way of life and worldview were justified and noble; it served them well in the face of challenges and became an indelible aspect of their identity. However, then as now, time and distance have widened attitudinal fissures where former mutual respect devolved into disdain and distrust. As these differences in cultural outlooks exist today, then how, and why, did Athens and Sparta resort to war? More importantly, what should we learn from it?

First, Thucydides identified fear, honor and interest as the roots of conflict. He knew each element had an escalatory effect with capacity to energize people to resist threats, real or perceived. Should an agenda be compromised, the sense of honor degrades. Once a people’s concept of honor of is threatened, collective fear rises to protect the societal framework. Fear, for personal safety or for traditional integrity, turns neighbors into “them” and fellow citizens into challengers. During the 2016 election and the weeks after its results, the continuing discourse among both sides of American society remains especially intense, divisive, and at times, despondent; a sign that the distance between interest, honor and fear are worryingly compressed.

Second, gaining and using a position of advantage over a rival will heighten interests and change a cooperative relationship into a more intense competition. After the 2008 elections, “blue” populations wielded the political leverage they gained and levied wholesale socio-ideological changes upon “red” areas akin to a modern Melian Dialogue where “the strong did what they could and weak suffered what they must.” “Blue” imposition of federal social agendas, boycotting of businesses and repudiation of contrary sentiments upended “red’s” traditional notions of self, its societal codes and faith in representative government. These actions and the effects of the 2008 economic recession exacerbated “red” fear and its reaction to support a presidential candidate who championed their specific grievances. In ancient Greece, Athens’ rivals reciprocated their unyielding forcefulness when fortunes reversed, raising the stakes for both contestants. Today, “red” and “blue” populations share these perspectives as both recent victor and vanquished.

Do these similar characteristic necessarily portend to war? Today, the thought of armed conflict between “red” and “blue” states is an implausible scenario. Thucydides, however, warns us to not discount the possibility entirely. Civil wars have their own specific origins, contexts and contributing factors. However, multiple variables—the diminishment of an external threat, the passage of time, changing economic fortunes and a nation with non-homogeneous cultures—provide a perspective.

Athens and Sparta maintained fifty years of peace between the defeat of Persian conquest and the start of the Peloponnesian War. For the United States, forty-nine years passed between the War of 1812 and America’s Civil War. In both examples, all four above-mentioned attributes existed. Additionally, a rational political decision by one side altered a tenuous balance of power, serving as a flashpoint for conflict. In ancient Greece, it was Athens’ alliance with Corcyra. For the United States, it was the determination to abolish slavery.

Certainly, half a century without foreign menace is not the singular yardstick to measure the beginning of a domestic war. It is conceivable, however, that in the span of two generations within a disparate society without a common threat to bind them, the raison d'etre for unity through collective security fades allowing internal energy to focus on the advancement of factional agendas.

As we approach the transition of the presidential administrations, twenty-five years will have passed since the Soviet Union’s dissolution on 25 December 1991. Coincidentally, today’s bifurcated regional political allegiance took shape after the Cold War’s end in the following 1992 presidential election. Within the passing of a single generation, the lines between America’s “blue” and “red” states grew more and more geographically distinct and culturally inflexible. A dynamic characterized by “blue” projecting its aspirations in the newly triumphant liberal world order as “red” areas became withdrawn and marginalized by the encroachment of foreign and non-traditional influences. Will the current divergent trajectory of “blue” and “red” continue through another generation? If so, which issue from the wide array of current and emergent challenges may be the pivotal decision for a domestic flashpoint?

In recent memory, exploring the nexus of regional grievances, cultural separation, political power and their consequences is an indulgent perspective America chooses when looking abroad. But, perhaps Thucydides’ perspective can provide us opportunity and encouragement to analyze America’s causes of strife, understand our domestic differences and close the socio-political gaps in our society. Thucydides, unfortunately, offered no solution to avoid conflict in future Athenian-Spartan parallels. He only recorded the harmful trajectory where societal divergence led Athens and Sparta to conflict. However, history is not prophecy and it serves only to illuminate a path, through analogy, for more current and dark times. This is precisely why our Founding Fathers read and regarded Thucydides’ writings. The Peloponnesian War served them an authoritative guide to better understand society and its tendencies in order to better navigate the perils of democratic governance in a new nation. With the assistance of history, will we be wise enough again to use it to shed light on our future?

Jeff Vandaveer is a fellow at the Atlantic Council.

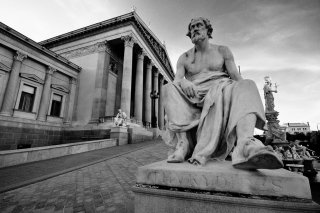

Image: Statue of Thucydides in Vienna. Flickr/Creative Commons/Chris JL