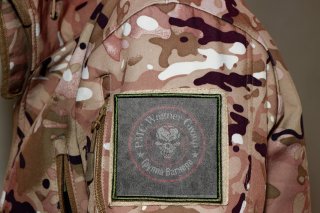

The Wagner Group’s African Empire

The Putin-Prigozhin deal that ended the mutiny should be viewed as a calculation of Wagner's importance to the Russian regime.

The short-lived revolt led by Wagner boss Yevgeny Prigozhin caused analysts far and wide to speculate about the future of the Wagner Group in Africa, arguing that its role on the continent is now in question. These assertions tend to overstate the current disarray inside the Kremlin and understate the importance of Wagner’s economic and geopolitical ventures to the war in Ukraine. While some might argue that Russian president Vladimir Putin’s decision to let Prigozhin off unscathed in Belarusian exile reflects the former’s weakening grip on power, the necessity of the Wagner network to the financial feasibility of the Ukraine “special operation” makes the decision appear more calculated.

The reality of the Russian war effort is that it relies on profits from Wagner’s African business ventures. With near total state control in the Central African Republic (CAR), a strong presence in Mali, Libya, and Sudan, and rumored military deployments in countries throughout the Sahel, including Burkina Faso and Chad, Wagner’s network in Africa is strong, multifaceted, and effective. But more importantly, it is a network partially built for mitigating the financial fallout of the Ukraine War—Moscow’s contingency planning.

Wagner secures payment for security services in unstable African nations through resource contracts, including gold and timber in CAR and oil in Libya, which is then funneled to Russia to support the war in Ukraine. In CAR, reports reveal that Wagner’s control extends to every sector of the economy—not only natural resources but also the sale of pedestrian products such as beer—reaping massive financial rewards for Moscow. Experts estimate that Wagner’s control of forestry and the Ndassima gold mine in CAR alone could produce billions of dollars in revenue. With these funds and more from Wagner’s entire African network, the failure of Western sanctions to deal a death blow to the Russian war effort in Ukraine is less puzzling.

The bottom line is that Putin needs Wagner—the group’s ventures are a critical lifeline for the war. And unfortunately for Putin, Prigozhin is the man that has ensured Wagner’s success. Prigozhin’s business model is one of the greatest contributions to Russia’s geopolitical goals in recent years. With Prigozhin dead or jailed, Putin would threaten the sustainability of Wagner’s model. Wagner forces loyal to Prigozhin may not accept a unilateral change in the group’s institutional hierarchy and organizational structure. Infighting for control and leadership would surely emerge, leaving its capacity to carry out critical operations and business ventures stymied. Thus, the decision by Putin to give Prigozhin the equivalent of a slap on the wrist emerged from a pragmatic recognition of the importance of Wagner’s activities to the Ukraine war effort. The deal is a sort of insurance policy that allows Putin to continue benefiting from Wagner in the short term while buying him time to reduce Prigozhin’s control of the empire without threatening the group’s operations.

But financial resilience is just one of many benefits Russia gains from Prigozhin’s strategic kleptocracy in Africa. Countries with a Wagner presence, including Mali and CAR, abstained from voting to condemn the Ukraine invasion. Meanwhile, disinformation campaigns throughout the continent foment strong support for Russia while exploiting anti-Western sentiment that has arisen in some parts of the continent, especially in Mali and the Sahel.

The Putin-Prigozhin deal that ended the mutiny should therefore be viewed, at least partially, as a strategic calculation by Putin. The vastness of the empire built by Prigozhin and carried out by Wagner throughout Africa should not be underestimated. Indeed, the group carries out economic, political, or military operations in at least a dozen African nations. For Putin, risking the collapse of that empire as his country fails to make progress in Ukraine would be misguided. Consequently, while Putin may force Wagner troops operating in Ukraine to integrate with the Russian army (or accept exile in Belarus), those operating throughout Africa will likely remain untouched as Putin works to wrestle control of the PMC from Prigozhin.

Analysts do correctly agree, however, that skepticism over Wagner's strategic value may preclude Wagner's expansion into new client nations in Africa, at least in the near future. Prigozhin’s mutiny may initiate a period of hesitancy towards Wagner partnerships among African leaders. However, suppose Wagner operations in current client states remain unchanged, as reported by Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov, and Russia continues to pump out disinformation campaigns. This period is sure to be short-lived.

For the US, the mutiny has thus gifted the Biden administration with a crucial, albeit small, window of opportunity to uproot Russia’s tightening grip on the continent, especially in the Sahel. Taking advantage of African hesitancy towards the Wagner Group post-mutiny can allow the United States to contest Russian influence on the continent. Efforts such as the approval of emergency humanitarian aid to Burkina Faso and Mali, which are facing highly neglected humanitarian crises, and the appointment of a Special Envoy for the Sahel, a position that has remained vacant since the administration took office, would ensure that the region remains a priority while offering insecure nations an alternative international partner.

As the world grapples with the immediate impacts of Prigozhin’s mutiny, The United States should avoid underestimating the strategic necessity of the Wagner Group in Africa for Russia. The lack of adequate engagement with African nations targeted by Wagner may prove to be the greatest folly of Western efforts to halt Russia’s war in Ukraine. Thanks to Prigozhin, a critical opportunity for the US to undercut the Wagner empire has opened, an opportunity that the US cannot overlook.

Shalin Mehta is an undergraduate at Rice University studying Political Science and Policy Analysis. His topics of interest include the Middle East, Africa, arms control, and peacebuilding.

Image: Shutterstock.