Introducing Mr. Trevor-Roper

Mini Teaser: For the great historian Hugh Trevor-Roper—whose poison pen spared no ego and whose toxic overconfidence relegated him to a perpetual almost-ran—refusing to become the false prophet of a grand new theory of history was his greatest triumph.

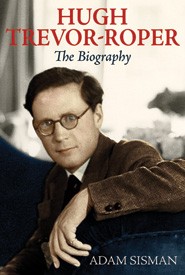

Adam Sisman, Hugh Trevor-Roper: The Biography (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010), 648 pp., £25.00.

[amazon 0753828618 full]THE OVERWEENING historian is a recurrent figure in British literature over the past century. Brilliantly talented and flamboyant, he—it is invariably a “he”—seeks, more often than not, adulation and celebrity as much as scholarly acclaim. In Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, for example, there is the historian as social climber. Mr. Samgrass of All Souls is an obsessive chronicler of the aristocracy. Eager to ingratiate himself with the cold and austere Lady Marchmain, Samgrass tries to rein in her son Sebastian, a wastrel who flits from one Oxford drinking club to the next, clutching his little teddy bear Aloysius. After Sebastian and his chums are arrested and jailed during one of their boozy, late-night escapades, Samgrass gets him off the hook by testifying not only that he possesses a faultless character but also that an exceptional scholarly career is endangered. A holiday trip to the Levant with Sebastian follows. His tutor loses sight of him in Athens, but “Sammy,” as Sebastian loves to deride him, continues his travels to Egypt on Lady Marchmain’s dime, only to be caught out once he returns after Christmas and visits the Brideshead manse where “guilt hung about him like stale cigar smoke.” Yet Samgrass contrives to remain indispensable to Lady Marchmain, basking in her and the castle’s reflected glory.

Then there is Anthony Powell’s opus A Dance to the Music of Time. It features the historian as a would-be man of political influence. The Oxford don Sillery’s weekly tea parties are where introductions are made and “young peers and heirs to fortune were not, of course, unwelcome.” Sillery is an inveterate schemer whose

understanding of human nature . . . [and] unusual ingenuity of mind were both employed ceaselessly in discovering undergraduate connexions which might be of use to him; so that from what he liked to call “my backwater”—the untidy room, furnished, as he would remark, like a boarding-house parlour—he sometimes found himself able to exercise a respectable modicum of influence in a larger world.

Most recently, Alan Bennett tackled this genre in his popular play The History Boys, which stars the historian as provocateur. Based largely on conservative historian Niall Ferguson, the protagonist is named Irwin. He explains to his young charges, “Truth is no more at issue in an examination than thirst at a wine-tasting or fashion at a striptease.” History is as much a sport as it is a profession for Irwin. The true danger isn’t being wrong; it’s being boring.

Where does Hugh Trevor-Roper—Regius Professor at Oxford, Master of Peterhouse, fellow of the British Academy and national independent director of the Times Newspapers, to name a few of his prizes—fit into this pantheon? To some extent he was a social climber, political intriguer and intellectual bomb thrower. For one thing, he could be a terrible snob. At his inaugural lecture for the Regius Professorship, he kept four rows in front empty for the aristocratic “quality” that he expected to arrive from London. “It was terrible to see aged dons and white-haired ladies rudely pushed away from these empty places,” his friend Isaiah Berlin observed in a letter. “In the end . . . nobody came and the seats were filled by plebeians.” It is also the case that he was constantly embroiled in academic feuds, curried favor with politicians such as Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and tooled around in a gray Bentley. Hauteur, ambition and zest for giving offense—these propensities earned him numerous enemies, who dubbed him “Pleasure-sloper.”

But he was also vied for by editors and publishers in England and the United States. The historian Christopher Hill announced in 1957 that “if Professor Trevor-Roper did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.” Trevor-Roper took care of that himself. He published his first book, at the age of twenty-five, on the seventeenth-century divine William Laud, archbishop of Canterbury in the reign of Charles I. Yet Trevor-Roper’s record included the failure, pointed out to him ad nauseam by his numerous detractors, to produce a magnum opus. Margaret Thatcher, who had bestowed upon him the title Lord Dacre of Glanton in 1979, later went on to harangue him as though he were a delinquent student in the summer of 1982 at a dinner party at 10 Downing Street: “So, Lord Dacre, and when can we expect another book from you?” He responded, “Well, Prime Minister, I have one on the stocks.” The Iron Lady’s response? “On the stocks? On the stocks? A fat lot of good that is! In the shops, that is where we need it!”

He married into the aristocracy (his wife was Lady Alexandra Henrietta Louisa Howard-Johnston, ex-wife of Rear Admiral Clarence Dinsmore Howard-Johnston and daughter of the controversial World War I general Douglas Haig). Like Mr. Samgrass, Trevor-Roper was never happier than when mingling with grandees in a country house. His wife’s dream came true when in 1983 she and her husband were invited to dinner with Queen Elizabeth—as a divorced and remarried woman, she had long been shunned by the highest reaches of the nobility. Redemption was at hand. But Trevor-Roper suffered a terrible blow when, at the behest of Rupert Murdoch, who had just acquired the Times, he hastily endorsed the Hitler diaries as authentic. Stern magazine, a popular weekly based in Hamburg, had first touted the diaries; they were quickly revealed to be forgeries, the work of the con man and Hitler admirer Konrad Kujau. A day before the Sunday Times was to run its excerpts, Trevor-Roper had second thoughts. It was too late. The “scoop” was published. Trevor-Roper’s enemies celebrated the seemingly permanent besmirchment of his reputation. In January 2003 Trevor-Roper died at the age of eighty-nine.

ENTER THE Trevor-Roper renaissance. A stream of his essays, books and letters is being posthumously released. Now Adam Sisman offers a major reassessment of Trevor-Roper’s reputation. Sisman, who knew Trevor-Roper personally, has assiduously researched his life. He is a lucid and engaging writer who brings out both Trevor-Roper’s pugnacity and his melancholia. Though Sisman refrains from rendering a verdict, his superb study suggests that Trevor-Roper was the most significant British historian of his generation.

Trevor-Roper was a frail and solitary child who immersed himself in books as much as he could. He grew up in the medieval town of Alnwick, where his father practiced medicine. His parents treated him and his siblings with frigid reserve and had no intellectual or cultural interests. His mother Kathleen was acutely conscious of social distinctions and refused to allow her offspring to mingle with their social inferiors. “The Trevor-Roper brothers,” Sisman reports, “remembered sitting on the garden wall, gazing down at the local children playing in the street.” As a nine-year-old, Trevor-Roper was enrolled at Stancliffe Hall, a preparatory school in Derbyshire that resembled something out of Charles Dickens, which is to say that the children were routinely punished for the most minor infractions.

Still, Trevor-Roper managed to win acclaim among his youthful peers by producing his first “major work,” Bible of Ghosts, which divided apparitions into their respective genera and species—complete with illustrations. A reprieve arrived when his parents decided to transfer him to Belhaven Hill across the border in Scotland, where Trevor-Roper learned Greek and Latin, invaluable training for his later career as a historian. Then, at age thirteen, he began public school. There he shone. Reading Homer was a revelation: “On I read, far past the appointed terminus, till late at night, fascinated; and all my leisure hours for long afterwards were spent in reading Homer, till I knew all the Iliad and Odyssey.” The sentiment, nostalgic and elevated, is rather reminiscent of Edward Gibbon’s recollection in his memoirs that when his father took him to visit a neighbor, he headed straight for the library and “was immersed in the passage of the Goths over the Danube, when the summons of the dinner-bell reluctantly dragged me from my intellectual feast.” Indeed Gibbon became Trevor-Roper’s idol, and The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire his stylistic bible. Gibbon united ironic detachment, scrupulous scholarship and a wider philosophical understanding of events, all traits that Trevor-Roper sought to emulate.

In 1932 Trevor-Roper was accepted into Christ Church. He was invited to meet with the dean, who, it was said, quivered with joy at the mention of a duke and tipped his hat to any undergraduate who was a member of the peerage. “Mr. Trevor-Roper,” he said, “I think that you come from Northumberland. I always say that so long as we have the Percys and the Cecils, Christ Church can hold up its head among the colleges of Oxford.” According to Sisman, “Hugh longed to escape from his own identity, which he despised as provincial and gauche.” He drank fine wines and champagnes. He dined on oysters. He threw lavish lunch parties. The bottle and the turf as well as riding to hounds became his new passions. He would disport himself in London, retuning to Oxford on the last train back known as the “Flying Fornicator.”

Pullquote: What Trevor-Roper admired was style and flair, the bold insight, not the tedious accumulation of detail for its own sake.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review