Assad's Uncertain Departure Path

Why actively seeking regime change in Syria would ruin Obama.

Yesterday I addressed the frequent absence of clarity, in public discussions of sanctions, regarding the objective that sanctions against any one regime are intended to achieve. Although this lack of specificity about the goal still characterizes all too many comments about sanctioning the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, official positions as well as unofficial commentary have been trending toward regime change as the explicit goal regarding Syria. The Obama administration has come close to this position but still pulls up short. White House spokesman Jay Carney, at his press briefing on Wednesday, talked again about how Syria would be “better off” without Assad, who has “lost legitimacy,” but Carney resisted an invitation to call more specifically for Assad to go.

Yesterday I addressed the frequent absence of clarity, in public discussions of sanctions, regarding the objective that sanctions against any one regime are intended to achieve. Although this lack of specificity about the goal still characterizes all too many comments about sanctioning the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, official positions as well as unofficial commentary have been trending toward regime change as the explicit goal regarding Syria. The Obama administration has come close to this position but still pulls up short. White House spokesman Jay Carney, at his press briefing on Wednesday, talked again about how Syria would be “better off” without Assad, who has “lost legitimacy,” but Carney resisted an invitation to call more specifically for Assad to go.

Even if regime change is the goal, another requirement to make meaningful any discussion of sanctions—or use of any other policy tool—is some specificity about how the current regime will go. Regime change encompasses a very wide range of scenarios, after all, from the ruler voluntarily stepping down to a mob storming the presidential palace, with many other possibilities such as an armed insurrection or a military coup. However worthy a goal Assad's departure may be, and despite the increasing sense that his days are numbered, it is still hard to identify a clear and plausible route for achieving that goal.

The popular uprising in Syria continues to impress with its extent and the courage of those participating in it. But as a recent summary in the Washington Post put it, “The protest movement remains without leaders and has offered no plan for replacing Assad, other than to continue staging protests.” The Syrian resistance does not seem on the verge of emulating its counterparts in Libya and starting a civil war.

Nor does there appear much likelihood of copying Egypt, where a united military decided its interests would be better served by pushing out the incumbent president. Any actions by Syrian military officers would immediately raise issues of sectarian divides that were not a factor in the Egyptian revolt. In particular, it is hard to envision what the role would be of Assad's fellow Alawites who disproportionately occupy key positions in the security services.

It's pretty easy to see why the Obama administration has been dancing around any explicit call for regime change in Syria. One, there does not appear to be a good path for accomplishing that goal. And two, Mr. Obama realizes that if he did explicitly adopt that goal, he would be criticized—by some of the same people who criticize him now for not being more explicit—for not accomplishing, or finding more active ways to pursue, a declared U.S. objective. The criticism would be rooted in the invalid but common idea that if there's something worth doing in the world, the United States ought to be the one to do it.

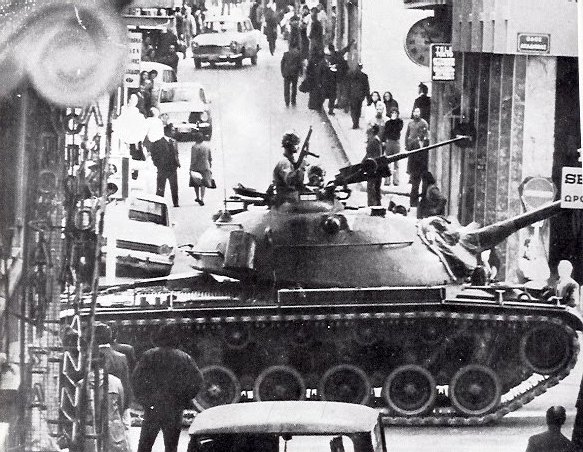

Image by Steve Jurvetson