Mohandas and the Unicorn

Mini Teaser: Gandhi cuts a saintly figure in the modern imagination. Joseph Lelyveld’s controversial biographical account presents a more dispassionate perspective of the Father of the Indian Nation. An exaggerated creation myth is revealed.

WHEN HE moved back to India at the start of the First World War, he took the sense of national cohesion he had developed in South Africa—joining himself to the cause of the masses he had initially spurned—and gradually turned the previously staid Indian National Congress into a popular movement. Gandhi became the figurehead—or incarnation—of India’s demand for self-rule. He wore the clothes of the poor and lived in the style of an ascetic, using the mode of Hindu renunciation in which a believer forsakes worldly and materialistic pursuits in favor of spiritual development. Disciples arrived. The daughter of a British admiral, renamed by him “Mirabehn,” shampooed his legs each night to soothe the marks left by those who had touched his feet in homage. His return to his homeland coincided with a change of tack in Whitehall, as “the gradual development of self-governing institutions” became government policy in India. At first, Gandhi put the same faith in this promise as he had in Queen Victoria’s proclamation and tried to recruit soldiers to fight in the war, arguing that helping the British in a time of need was “the straightest way” to self-rule. But it became clear that his opponents were thinking in terms of decades or even centuries before India would be ready to govern itself, while Gandhi and his colleagues were thinking in years.

In the succeeding period, one of his key methods was to alter the focus of his campaigns as he went along: spinning, cow protection, caste reform, village living, the reestablishment of the recently abolished Islamic caliphate—any of these might be presented as his chief objective, working on the precept that true self-rule was impossible without social change. Underlying this was a pragmatic need to bridge contradictions and to appeal to as many interest groups as possible. His backing for the thugs who ran the caliphate movement in India seems in retrospect to have been a cynical way of attracting mass Muslim support. In several cases, he would appropriate a minority and sideline its own leaders. When faced in negotiation with Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar, arguably an equally iconic social activist, who spoke for India’s 60 million “untouchables,” Gandhi simply announced: “I claim myself in my own person to represent the vast mass of the untouchables.” His ability to change the rules as he went along and to play on ambiguity was consistent; sometimes he would disappear when he reached an impasse, only to reappear with a fresh mission. Obsessed throughout his life with control of the body, diet and the need to eliminate sexual desire, Gandhi became in his later years—after he had formally retired from the Indian National Congress—increasingly troubled and eccentric, a spiritual or moral figure rather than a political actor. A new generation made the proximate decisions which led to Indian independence, and he fell to a Hindu assassin’s bullet soon afterward.

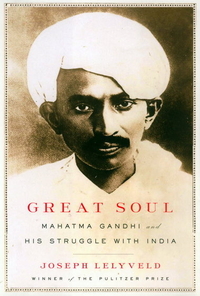

THE VICTORS write history, and although Lelyveld offers sharp rewrites, he cleaves broadly to the iconic version of Gandhi’s life propagated by the Indian National Congress—namely that he was a mahatma, or “great soul.” Instead of being seen as a particularly brilliant political maneuverer, he is examined and interrogated more as a unicorn, a one-off, a man who must be judged by a different standard than other nationalist leaders. But if you look at Mohandas Gandhi dispassionately, the important constituent parts of his creation myth do not hold together.

Take the episode at Pietermaritzburg. As Lelyveld observes, it is often forgotten that Gandhi’s demand to be allowed to travel in a first-class carriage was accepted by the railway company, and he boarded the same train the following night under the protection of the stationmaster. The privilege was essentially financial; aged twenty-four, he was rich enough to place himself in a category separate from the indentured “coolie.” Rather than marking the start of a campaign against racial oppression, as the legend has it, this episode was in fact the start of a campaign to extend racial segregation. Throughout his time in South Africa, Gandhi was adamant that “respectable Indians” should not be obliged to use the same facilities as Africans. He petitioned the authorities in the port city of Durban, where he practiced law, to end the indignity of making Indians use the same entrance to the post office as blacks, and counted it as a victory when three doors were introduced: one for Europeans, one for Asiatics and one for Natives. Whichever way you parse it, Gandhi’s views on Africans do not make happy reading. His writings contain references to “raw Kaffirs” and their “indolence” and to the fact that he thinks they are “troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals.” But perhaps more important than the words of abuse—which might have been written in haste, or in a particular context—is that however hard you hunt in the archives, Africans remain invisible in Gandhi’s writings about Africa. As Lelyveld concludes, reluctantly, “In the several thousand pages Gandhi wrote in South Africa . . . the names of only three Africans are mentioned. Of the three, he acknowledges having met only one.” The explanation for this may be quite simple: antiblack prejudice was and is endemic in India.

If, as a privileged Gujarati born in 1869, Gandhi harbored the bias of his background and generation, we should hardly be surprised. He was not, contrary to later reworkings of his story, a liberal: he liked to lay down rules, was often undemocratic and his ideas were in certain respects traditionally Hindu. Lelyveld describes him traveling to the Godavari River in central India after his return from England in order to go through purification rituals, to rid himself of the pollution. His views on caste were malleable, and his campaigns against untouchability were tempered by circumstance. He never accepted Ambedkar’s demand for constitutional protection and distinct civic rights for those outside the caste system; instead Gandhi insisted the Hindu majority would bestow favors upon them. When a deputation of “untouchables” wanted to join his organization the Harijan Sevak Sangh, dedicated to uplifting the Harijans (meaning “children of god”—a phrase now rejected as patronizing), Gandhi told them it would not be permitted:

The Board has been formed to enable savarna [upper-caste] Hindus to do repentance and reparation to you. It is thus a Board of debtors, and you are the creditors. You owe nothing to the debtors, and therefore, so far as this Board is concerned, the initiative has to come from the debtors.

It was typical Gandhian logic, and the Harijans went away defeated. Ambedkar suggested angrily that the whole purpose of Gandhi’s board was “to create a slave mentality among the Untouchables towards their Hindu masters.” It is not insignificant that former untouchables in India today often have great hostility toward Gandhi and the way in which he treated their emerging community leaders. In his approach to Indian Muslims, he had something of the same attitude. Although at times of bloodshed he would use public fasts and marches effectively to promote communal harmony, Gandhi’s underlying precept was majoritarian, believing that Hindu compassion and goodwill rather than structural safeguards would bring India’s large Muslim minority into a wider national fold. As an idea it was imaginative, but many followers of Islam found the Indian National Congress before independence to be, in practice, redolent of Hindu culture—and upper-caste culture at that. Gandhi combined orthodoxy and radicalism. If he had not been, in many respects, an identifiable Indian type—the Hindu renunciate—it is unlikely he would have gathered such extensive support for his cause in an ethnically and linguistically varied land like India. By the 1930s, most Muslim politicians of national stature were migrating to other parties, and the demand for a separate homeland grew, leading finally to the creation of Pakistan.

GANDHI’S GREATEST achievement was to invent a new form of public assertion that could, under the right circumstances, change history. His method depended ultimately on the existence of a democratically responsive government. He figured, from what he knew of Britain, that the House of Commons would only be willing to suppress uprisings in India to a limited degree before conceding. And so he launched a vast movement of noncooperation to push for Indian independence—the British responded with violent crackdowns; they arrested Gandhi and tens of thousands of protesters, even throwing most of the Indian National Congress leadership in jail during the Second World War. By 1947, nearly bankrupt and dependent upon American loans, the British caved. Had Gandhi been up against a different opponent, he would have had a different fate. When the former viceroy of India, Lord Halifax, went to see Adolf Hitler in 1938, the German leader suggested he should have Gandhi shot; if nationalist protests continued, members of the Indian National Congress should be killed in increments of two hundred until the problem went away.

During the British general election last year, the outgoing prime minister, Gordon Brown, had a pavement encounter with an angry voter, Gillian Duffy, who berated him about pensions and taxes. It was the sort of televised public humiliation that is now obligatory every few years in a democracy, as the leader is shouted down by a “normal” person and obliged to pretend to listen politely while the cameras are rolling. Unfortunately for Mr. Brown, he was still wearing a radio microphone when he got in his car to escape and was heard to say of his tormentor: “Och, she’s just this sort of bigoted woman.” For several days afterward, Brown’s groveling apology to Mrs. Duffy, first to the media and later in person, became the main topic on the news.

Pullquote: Gandhi was not, contrary to later reworkings of his story, a liberal: he liked to lay down rules, was often undemocratic and his ideas were in certain respects traditionally Hindu.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review