Qutb and the Jews

Mini Teaser: The conventional wisdom says Sayyid Qutb is the forefather of modern-day Islamic fundamentalism. What is less known is how the thinker's intense anti-Semitism and contempt for female sexuality contributed to this vulgar worldview.

John Calvert, Sayyid Qutb and the Origins of Radical Islamism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 377 pp., $29.50.

[amazon 0231701047 full]

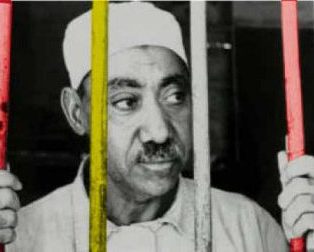

THE COVER of John Calvert’s book parades the face that launched a thousand suicide bombers. Sayyid Qutb, the major ideologue of modern, ultraviolent Islamic fundamentalism, is staring through bars, probably during his Cairo trial in April 1966, shortly before his death sentence was pronounced. Bushy eyebrows, a full, dark, graying moustache, large brown eyes, inquisitive, wary, worried. But by some accounts, he was looking forward to his martyrdom: “I have been able to discover God in a wonderful new way. I understand His path and way more clearly and perfectly than before,” he wrote to a Saudi colleague in June. He was hanged by the Nasser regime, along with two fellow Muslim Brotherhood activists, in the early morning hours of August 29.

A recent profile of Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, says that he has spent much of his time in the American detention facility at Guantánamo Bay reading Qutb. Apparently, so have many others among the fundamentalists wreaking havoc in Middle Eastern, Far Eastern and Western cities in recent decades. Qutb is the man whose books, written as he was edging toward Islamism in the late 1940s and after his “conversion” during the 1950s, explain why Muslims must wage jihad against both the “Near Enemy”—the Western-aligned and Western-influenced regimes in the Arab world—and the “Far Enemy”—meaning the West itself, especially the United States.

Qutb was born in 1906 into a lower-middle-class family in the Nile valley village of Musha, near Asyût. He was educated at a secondary school and a teacher’s training college in Cairo, and subsequently earned his living as a teacher, Education Ministry official, journalist, novelist and Islamic thinker. As a young man he developed strong nationalist, anti-imperialist convictions; in his forties, he gradually edged toward an Islamist worldview, seeing Islam as both the means and goal of life on earth. (It was, as well, a tool which would facilitate liberation from Western colonialism; secular nationalism and the governments it spawned—Nasserist, Baathist or whatever—would not do the trick, nor would they provide the social justice and harmony that he espoused.)

The West was both evil and the source of evil, polluting and emasculating the Islamic world, culturally and politically. As Qutb grew up between the world wars in British-dominated Egypt, Western influences were all around. He acutely felt the humiliation of colonialist contempt—they “ran over Egyptians in their cars like dogs”—and in his maturity, repaid it with contempt, and a rejection, of his own. As he put it in 1943: “This [Western] civilization that is based on science, industry, and materialism . . . is without heart and conscience. . . . It sets forth to destroy all that humanity has produced in the way of spiritual values, human creeds, and noble traditions.” He contrasted Islamic society’s religiosity and morality with the West’s “materialism,” though in the 1940s and 1950s he became highly critical of Muslim Arab societies, deeming them by and large jahili (ignorant of God’s truth) if not downright kafiri (apostatic). A few years later he wrote of the “struggle between the resurgent East and the barbaric West, between God’s law for mankind and the law of the jungle.” But Qutb, in the immediate post–World War II years, though hateful of Zionism and its Western backers, admired the two right-wing Zionist militia groups, the Irgun and the LHI (the Stern Gang), because of the success of their assassination and terror campaigns that had given the British a bloody nose.

Qutb’s anti-Westernism was reinforced by his two-year sojourn in the United States between mid-1948 and mid-1950. He was sent there by the Egyptian Education Ministry to study the American education system—and learn English. Not everything he reported then, or later, about the United States is credible; employees in a Washington, DC, hospital, he claimed, rejoiced upon hearing of the assassination in Egypt in February 1949 of the founding head of the Muslim Brotherhood, Hassan al-Banna. An unlikely story, to say the least. But he certainly came away from the visit with a sense of American racism, reacting no doubt to both real and imagined slights. “They talk about coloured people, like the Egyptians and Arabs generally, as though they were half human,” as he put it in an article after his return to Egypt. “Their swaggering in the face of the rest of the world,” he was to write, “is worse than that of the Nazis.” And so, he concluded (and the distance from here to 9/11 is quite short):

The white man, whether European or American, is our first enemy. We must . . . make [this] the cornerstone of our foreign policy and national education. We must nourish in our school age children sentiments that open their eyes to the tyranny of the white man, his civilization, and his animal hunger.

By “animal hunger” he was referring to what he regarded as the sexual promiscuity that he encountered at every turn. Never mind the nightlife of New York or the mores of Los Angeles. Even a church social he attended in Greeley, Colorado, was execrated:

The dance hall was illuminated with red, blue and a few white lights. It convulsed to the tunes of the gramophone and was full of bounding feet and seductive legs. Arms circled waists, lips met lips, chests met chests, and the atmosphere was full of passion.

American women in general he described as having “thirsty lips . . . bulging breasts . . . smooth legs,” all topped off by “the calling eye . . . [and] the provocative laugh.”

Indeed, after returning to his homeland, he had nothing good to say of the United States—whether it be about the climate, American sloth or the unattainability of a good haircut. Qutb saw it all as shallow and obsessed with vile concepts of materialism and brute strength. American civilization was so deformed that, “when the wheel of life has turned and the file of history has closed, America will have contributed nothing to the world heritage of values.” (Qutb’s summation reminds one of a recent declaration by a former archbishop of Canterbury that the Muslim Arab world has contributed nothing of worth to mankind in the past seven hundred years.)

BUT WESTERN sinfulness was not restricted to their own lands. America was busy spreading its values eastward, polluting (and thus enfeebling) the Muslim world. In addition to neutering its males by denying them power, the West was subverting the traditional (inferior) role of women; exporting the notion of feminine equality, which was leading to “discord” (fitna) in Muslim societies. Women were suitable only for domestic, not public, responsibilities, thought Qutb. Moreover, unchecked, now-liberated feminine sexuality was tempting men into sin, corrupting the social order.

As history professor John Calvert demonstrates in this biography, quoting from Qutb’s writings, the would-be-nationalist-reformer-turned-Islamist was fixated on the malign power of feminine sexuality years before reaching America’s shores; the journey to the land of the infidels only secured a hatred that would later spawn violence in so many. He never married and, Calvert opines, “probably died without ever having had sexual relations.” Perhaps he never found a woman who was sufficiently unsullied; perhaps women found him unattractive. Whatever its origins and development, a clear psychopathology was at work here. Ever repressed, Qutb both idealized women and was deterred by their unleashed sexuality. He was to inveigh against Egypt’s popular singers that they debased true love and against businesses, which, to make a profit, splashed “naked thighs and protruding breasts” across magazine covers. He said that this sapped the will of the nation (an image reminiscent of General Jack Ripper in Dr. Strangelove, who saw all around him a Commie plot to pollute Americans’ “vital bodily fluids”). Sexual permissiveness contributed to the decline of Athens, Rome and Persia. Licentiousness, Qutb declared, was “now working for the destruction of Western civilization. . . . France is foremost because she took the lead in shedding moral inhibitions. She succumbed in every war she fought since 1870.” (Presumably, the Arab states’ loss of all their wars since their emergence—against Israel, the United States, etc.—was due to their corruption by the West.)

Calvert doesn’t elaborate on this point, but sex does seem to be at the heart of so much modern terrorism. Frustrated male and female sexuality, borne of socially ordained repression and a sense of sinfulness and self-loathing, without doubt provides one key to understanding our time’s Islamists. It is no accident that the prize of seventy-two dark-eyed virgins is held out to the young male recruits as they strap on their explosive vests; and that Palestinian women suicide bombers more often than not are spurned or abandoned by their actual or prospective spouses just before setting out on missions. Energies that otherwise would have been directed toward sex are diverted to violence.

And so inbred is the hatred of their own desires, nurtured by the repressiveness of Muslim societies, that when they come in contact with the sexual allure of the West, that, too, can set the murderousness in motion. The Hamburg-cell bombers and the pilot trainees who eventually flew into the Twin Towers often spent their evenings with German and American girls in sleazy bars. This apparently induced both loathing of the temptresses, who represented the West, and self-loathing resulting from the temptresses’ success in subverting their Islamic values and identities. Palestinian Hamas’s pamphlets frequently excoriate the loose morals purveyed by Israeli society and culture as one reason for extirpating Zionism from the midst of the believers, whom they contaminate by their very existence.

THE WEST’S pollution of the lands of Islam was a main reason for Qutb’s propagation of jihad. The Koran enjoins the faithful to fight those who “believe not in Allâh . . . nor in the Last Day . . . nor forbid that which has been forbidden by Allâh and His Messenger . . . and those who acknowledge not the religion of truth.” While some Muslim exegeses maintained that jihad must be joined only in defense of the Islamic realm or people, the thrust of the traditional Muslim interpretation, to which Qutb also adhered (certainly in his last years), was that jihad should be waged against all unbelievers defensively and offensively in order, ultimately, to bring all the world’s peoples into the embrace of Allah. Or as Qutb put it: “If we insist on calling Islamic jihad a defensive movement, then we must change the meaning of the word ‘defense’ and mean by it ‘the defense of man’ against all those forces that limit his freedom.” (Qutb always insisted that real freedom was achieved only through submission to Allah and wholehearted acceptance of the truth of Islam.)

Qutb, says Calvert, saw jihad as the instrument of an essentially expansionist Islam. “For Qutb, as for the classical jurists, it is important that Islam be elevated to a position of power over [all] the peoples of the earth.”

This was the strategic vision. But as Calvert points out, Qutb in the 1950s and 1960s was aware of the weakness of contemporary Muslim societies and hence strove, in the first instance, to build up Muslim power and the cadres of the Islamic revolution, and then to tackle the “Near Enemy”—the Western-affiliated regimes—before dealing with the source of evil itself. (Qutb’s pupils, Ayman al-Zawahri, who studied directly under Qutb’s brother Muhammad Qutb, and Osama bin Laden, preferred to reverse this strategy for al-Qaeda: They reasoned that it was best to go for the “Far Enemy” first, which, once weakened, would be unable to prop up the Saudi and Egyptian governments. Then all would more easily fall before the Islamist storm.)

CALVERT PROVIDES a good review of Qutb’s intellectual and ideological development, but there is one serious elision, and this constitutes a major failing: the book does not thoroughly, let alone persuasively, deal with Qutb’s anti-Semitism. In the end, Calvert simply dismisses Qutb’s anti-Jewish assertions as an idiosyncratic matter of a personal, “‘paranoid’ style”—instead of squarely facing up to the wider implications of what Qutb’s case tells us about Islam and the Jews. Calvert uses the standard (historically inaccurate) apologetic arguments that the Islamic authorities never adopted a “persecutory posture” toward their Jewish minorities and that Jews, accorded a “relatively secure position,” were “tolerated” in Muslim societies, as compared with how their coreligionists fared in the Latin West. The histories of Muslim-Jewish relations in the lands of Islam by scholars such as Norman Stillman and Bernard Lewis do not support this description.

Calvert never says, simply, that Qutb was an anti-Semite; perhaps it is politically incorrect to forthrightly accuse a major Muslim thinker of such a predilection. But “the Jews” appear to have been important, if not central, to Qutb’s worldview, at least after the Arab disaster in Palestine in 1948. From that year onward Qutb was wont, like most contemporary Islamists, to refer to the Muslims’ “Crusader [i.e., Christian] and Zionist” enemies.

But Qutb’s anti-Semitism was religious and deep-rooted, originating in the Koran and its descriptions of Muhammad’s antagonistic relations with the Jewish tribes of Arabia (who simply rejected the Prophet and his message and were consequently slaughtered, enslaved or exiled by him), not in the contemporary struggle with Zionism. (Though the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict, no doubt, exacerbated his anti-Jewish prejudices. He often compared what he saw as Jewish misdeeds in seventh-century Hejaz—the Jews turning their backs on divine revelation, trying to poison the Prophet and fighting the believers—and twentieth-century Palestine.)

In or around 1951 Qutb published an essay entitled “Our Struggle with the Jews” (reprinted as a book by the Saudi government in 1970). Calvert devotes a paragraph to this screed—but would have done well to elaborate further. In the essay, Qutb vilified the Jews, in line with the Koran, as Islam’s (and Muhammad’s) “worst” enemies, as “slayers of the prophets,” and as essentially perfidious, double-dealing and evil.

Qutb uses Nazi language. The Jews, he wrote:

Free the sensual desires from their restraints and they destroy the moral foundation on which the pure Creed rests, in order that the Creed should fall into the filth which they spread so widely on the earth. They mutilate the whole of history and falsify it. . . . From such creatures who kill, massacre and defame prophets one can only expect the spilling of human blood and dirty means which would further their machinations and evil.

Moreover, Jews, by nature, are “ungrateful,” “narrowly selfish” and “fanatical.” He continued, “This disposition of theirs does not allow them to feel the larger human connection which binds humanity together. Thus did the Jews (always) live in isolation.”

In his essay, written six years after the Holocaust, Qutb stressed that the battle with the Jews—now in the guise of Zionists—had raged for 1,400 years and continued. Typical of his thinking and style of argumentation is the following mendacious anecdote, proffered in a footnote: “While entering (Old) Jerusalem in 1967, the Jewish armies shouted, ‘Muhammad died and had fathered only daughters.’”

IN HIS introduction, Calvert presents Qutb as a supremely moral being. He was bent on propagating Allah’s message to humanity, and that message was beneficent and moral. So Calvert asserts: “Qutb never would have sanctioned the killing of civilians, which several of the militant groups committed. . . . Al-Zawahiri’s bloody war against the ‘Far Enemy’ took radical Islamism to a place that Qutb had never imagined.” Perhaps, in truth, Qutb’s imagination never technically went as far as envisioning large Muslim-piloted jet aircraft exploding into infidel skyscrapers. But the question, really, is whether he would have sympathized with and supported al-Qaeda’s campaign against the West. It is pointless to speculate. But the things Qutb wrote in his lifetime about the West and the United States (and the Jews) sound not very different from the contemporary railing of al-Zawahri and bin Laden.

Benny Morris is a professor of history in the Middle East Studies Department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. His most recent book is One State, Two States: Resolving the Israel/Palestine Conflict (Yale University Press, 2009).

Correction: The passage “While entering (Old) Jerusalem in 1967, the Jewish armies shouted, ‘Muhammad died and had fathered only daughters.’” appears as a footnote in the Saudi edition of "Our Struggle with the Jews." But it was added, posthumously, by the editor (see Ronald L. Nettler's Past Trials and Present Tribulations, which contains the essay's translation into English), and I should have noted that.

Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review