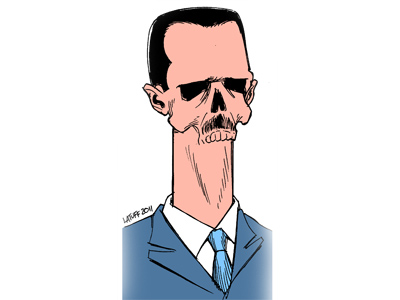

Assad the Survivor

A strategic shift shows Syria's president may be as clever as he is brutal.

After two years of armed conflict, is the Syrian army finally close to collapse? This question, frequently posed during the war, has gotten much louder over the past month as the anti-Assad rebellion increases its military effectiveness and becomes more audacious in its messages on social-media sites. For those who have been tracking the conflict for the past twenty-five months, the strength of the Syrian army is the best barometer for measuring Assad’s staying power.

After two years of armed conflict, is the Syrian army finally close to collapse? This question, frequently posed during the war, has gotten much louder over the past month as the anti-Assad rebellion increases its military effectiveness and becomes more audacious in its messages on social-media sites. For those who have been tracking the conflict for the past twenty-five months, the strength of the Syrian army is the best barometer for measuring Assad’s staying power.

Judged from the latest events on the ground, there is a strong feeling worldwide that Bashar al-Assad’s security forces are nearing the breaking point. For the first time since the civil war began, the Syrian army last month lost control of a provincial capital, the city of Raqqa, after a sustained offensive from rebel fighters—some of whom were associated with the extremist Jabhat al-Nusra. In the country’s northeastern and eastern sectors, antigovernment elements are beginning to establish a temporary political administration to fill the void of a retreating regime. And in a new development, Syrian rebel forces have opened up a new front near the Golan Heights and along the Syrian-Jordanian border, two areas relatively close to the capital of Damascus.

When coupled with a desertion rate that continues to thin out the Syrian army’s rank-and-file, an overtaxed logistics system for sustaining the army in the field, and the hundreds of fatalities that the Syrian government suffers every month, it is tempting to say that the backbone of Assad’s strength—the army, intelligence and security services—will not be able to hold on much longer. Consider the actions of Syria’s Grand Mufti, Sheikh Ahmad Badr al-Dine Hassoun, who pleaded last month for Syria’s young men to fulfill their religious duty by joining the army. Translation: the Syrian armed forces are in a tough spot, and need more men to fight.

Yet, as stressed as the Syrian army now appears after two years of trying to contain hundreds of thousands of dedicated anti-government fighters, we should not hastily conclude that Bashar al-Assad is on his way out, as the Director of National Intelligence James Clapper hinted during testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee last month.

Progovernment forces have demonstrated a keen ability to adapt their techniques, conserve their firepower, and change their military plans to meet the changing strategic environment. More importantly, the Syrian army has demonstrated a willingness to escalate the use of force, employ destructive weapons systems and launch indiscriminate ballistic missiles.

Early last year, when a systematic campaign of destruction on the rebel-controlled district of Baba Amr failed to end opposition resistance, the Syrian army increased its firepower by deploying its fleet of helicopter gunships. When helicopters failed to do the trick, fixed wing aircraft and fighter jets were added to the mix, resulting in the deaths of thousands of additional civilians and culminating in an incredibly bloody summer.

In the fall and winter of 2012, when the Free Syrian Army made minor inroads in Aleppo and encroached ever closer to Damascus, the regime opted to give up on securing the entire country. Knowing that the insurgency was too strong in Syria’s north and east, Bashar al-Assad chose to play the long game by consolidating his forces in areas of the country considered vitally important for the regime’s survival: Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Hama, and the Alawite coast. As the Institute for the Study of War’s Joseph Holliday has illustrated in his latest report, the Syrian regime made the judgment that controlling the entirety of Syria was no longer possible. It was considered possible, however, to ensure that neighborhoods supportive of the government have sufficient resources to defend themselves. Building progovernment militias in local villages, arming Syria’s minority communities to fight a Sunni rebellion, and holding the key corridor from Damascus to the northwest coast is now far more important than killing every insurgent and controlling every town.

Before the international community writes Bashar al-Assad off, it should realize that a desperately strained Syrian military is not necessarily defeated. Assad maintains the solid loyalty of much of the armed forces, with a significant portion of them now fighting to thwart or delay what could be a vengeful, Sunni-led, post-Assad order after the war ends.

While he may not be able to extinguish the insurgency completely or control the entire country as he once did, Bashar al-Assad still has enough firepower and men to continue the conflict through the year. But Assad recognizes that cutting the army’s losses in the field, rallying his support base, and narrowing the mission are key to ensuring that the regime can fight on.

Daniel R. DePetris is a researcher at Wikistrat, Inc. The views expressed do not represent the views of Wikistrat and are those of the author alone.

Illustration by Carlos Latuff.