Ukraine’s Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace

Kiev thinks it’s ready to face an endless list of enemies. But it can’t.

By tradition, the Ukrainian political season begins the week after independence day—August 24. This year’s celebration was especially poignant, as it marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of Ukraine’s declaration of independence.

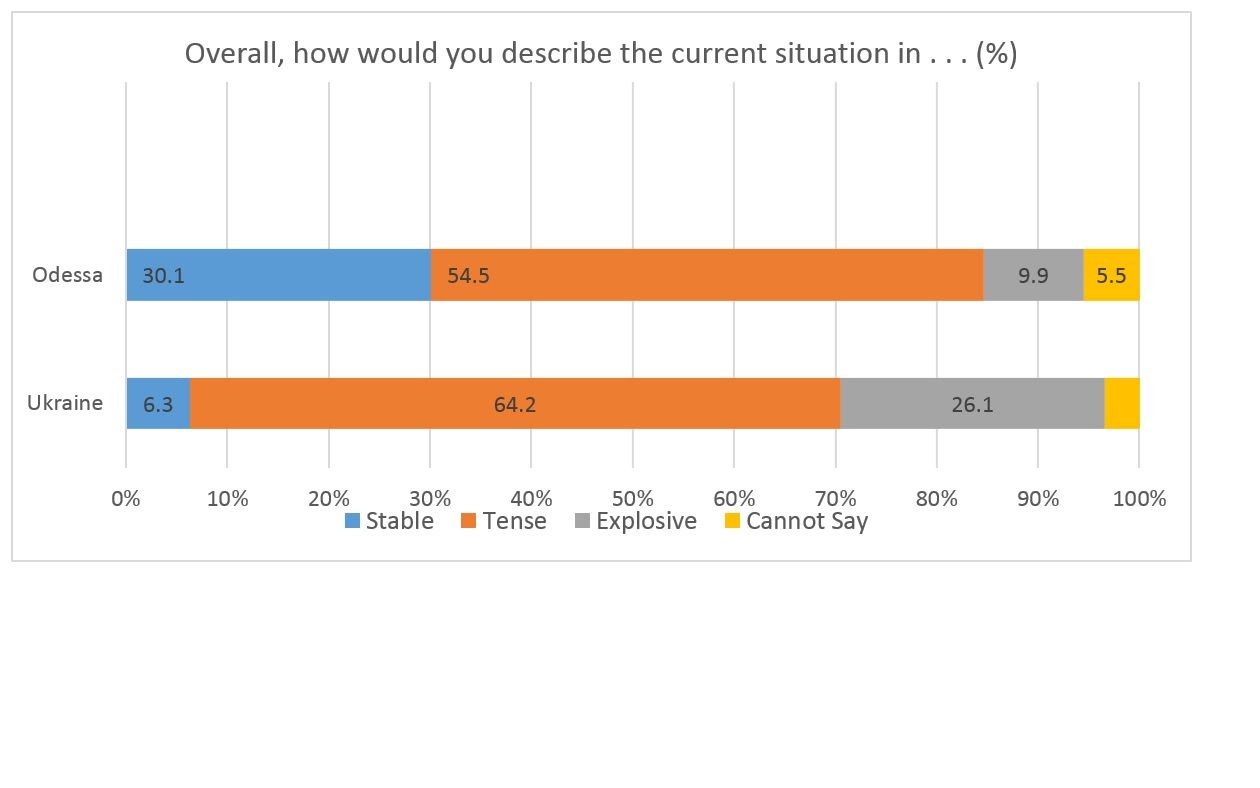

What was the public’s mood on the eve of this silver anniversary? A survey conducted this August by SOCIS, one of Ukraine’s best known sociopolitical research and marketing companies, provides a rather striking answer.

The survey, which was conducted in Odessa, Ukraine’s third-largest city, suggests that over half of Odessans describe their city as “tense,” while nearly ten percent say it is “explosive.” But even more interesting is that Odessans view the situation in Ukraine overall as much worse, with over ninety percent describing it as either “tense” or “explosive”!

Lest readers think that Odessa is an anomaly, I should point out that these results do not differ substantively from surveys conducted in February or June 2016, which show a steady decline in public trust in government since the 2014 Maidan uprising.

How did things get so bad? Part of the fault certainly lies with the IMF’s austerity recommendations, which the vast majority of Ukrainians view as both harmful and pointless. But no downward spiral in public confidence could ever be so complete without the connivance of government officials. To put it bluntly, government policies have seemed, at times, almost intentionally designed to fuel public anger.

A good example is the policy of actively curtailing Russian investment in Ukraine. While this has reduced Russia’s economic influence in the Ukrainian economy, as the government intended, in the absence of commensurate Western investment to replace what was lost, major industries have collapsed, and the country’s standard of living along with them. If the country continues on its present course, Odessa’s reformist governor Mikheil Saakashvili has noted sarcastically, Ukraine will not reach the level of GDP it had under former president Viktor Yanukovych for another fifteen years.

People might even be willing to view this as a necessary sacrifice in times of war, but for the fact that Ukrainian oligarchs often continue to line their own pockets by doing business in Russia. This includes President Petro Poroshenko himself, whose personal wealth increased sevenfold in 2015.

Another source of public frustration is the new quotas for the use of the Ukrainian language. According to the law signed on July 6, the percentage of total content in Ukrainian in radio and television programs must be raised to 60 percent. For some reason, special attention was paid to songs, of which 35 percent must be sung in Ukrainian during peak listening hours within three years. Broadcasters failing to comply will face a fine of 5 percent of their license fee.

Given the sheer size of the Russian-language market, Russian has always been preferred in the Ukrainian entertainment industry. Ukrainian nationalists see this as a problem, but instead of making the use of Ukrainian a more attractive choice by providing financial support for Ukrainian-language entertainment, the government has decided to punish the use of Russian—which, just a few years ago, was the language preferred by 83 percent in a Gallup survey. If the movie industry’s past experience is any guide, the results of this latest initiative will be a decline in domestic sales, a rise in bootlegged entertainment from Russia and no perceptible shift in people’s linguistic choices.

Finally, this summer the government decided to “de-Communize” local place names, often with undisguised contempt for the opinion of the local population. In the cities of Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnipro) and Kirovograd (now Kropyvnytskyi), surveys showed large majorities in those cities rejecting the government’s name choice and, if the name had to be changed, preferring the czarist-era names. The parliament rejected this option out of hand.

The current speaker of parliament, Andriy Parubiy, seemed genuinely outraged that local residents felt they should be consulted on the matter at all. Recounting how his grandmother used to tell him about the “Muscovite occupiers” who had killed millions in eastern Ukraine and then repopulated the region with others, he added: “And now you appeal to us on behalf of the local population? And now you appeal to us based on the opinion of the people who live there?” All eastern and southern Ukrainians were told, in effect, that their voices had no right to be heard in the national parliament, because they were, presumably, the descendants of “Muscovite occupiers.”

Parubiy later described de-Communization as the parliament’s main achievement this session, but in reality nothing has been settled. The parliament’s decision will be challenged in the courts for many years to come. Indeed, the most notable impact of the government’s ham-fisted efforts to reeducate its own citizens has been to relaunch the once discredited Opposition Bloc.

Meanwhile, bad economic news keeps piling up. In September, right around the time that the new session of parliament starts, people will be receiving their electricity bills, at a tariff rate that has just increased by 25 percent. This follows repeated hikes in utilities, which 80 percent of Ukrainians say they already cannot afford.

In Kiev, which is by far the wealthiest city in Ukraine, payment arrears for electricity have risen by 32 percent since the beginning of this year. If the city’s electricity provider, Kievenergo, should one day refuse service for nonpayment, the capital city would quickly shut down.

Then there is the matter of the third tranche of the IMF’s four-year $17 billion bailout program, which has been held up for over a year. The Ukrainian government, however, went ahead and included these funds in this year’s budget anyway. Without them, as much as 15 percent of current budget allocations may have to be sequestered, which would lead to national catastrophe. Even so, in a sign of how utterly frustrated many reformers feel, the once staunchly pro-Maidan Evropeiska Pravda published its first ever editorial on August 15, calling upon Western leaders to deny any further financial support to Ukraine until the government actually starts implementing some real changes.

In sum, the perfect political storm is brewing, and it is hard to see how the current government can get through the fall without new parliamentary elections. But with or without elections, the situation has become so dire that it would not take much to upset the whole political apple cart.

Radical nationalists, along with armed volunteer activists returning from the frontlines, certainly seem to be doing their very best to tip it, recently firebombing Inter, the country’s most popular television channel. Both groups thrive on the current chaos, so their interests overlap in keeping this, and any future government, weak and off balance.

The horrific crimes for which members of “Tornado,” the special police unit for eastern Ukraine established by Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, are now under indictment are thus not an anomaly, but a logical consequence of the resort to violence rather than dialogue in dealing with popular discontent in eastern Ukraine. As Avakov so disingenuously noted back in June 2014, at the outset of the military campaign in the east, an added benefit of war is that it can have a “cleansing” effect on the nation.

This explains why the Party of War in Ukraine—a group that includes such high profile personalities as the minister of the interior, the speaker of parliament, the head of the National Security and Defense Council and the former prime minister—has shown so little qualm about eastern Ukraine being liberated militarily. Some even insist that the struggle must some day be carried into southern Russia—to liberate the “authentic Ukrainian regions” of Voronezh, Kursk and Krasnodar.

What incumbent politician would espouse such lunacy? For one, the current head of military-civilian administration for Donbass, Pavel Zhebrivsky. He was appointed a year ago by President Poroshenko to govern this war-torn land and to win back the hearts and minds of the local population.

He began doing so by calling for the expansion of martial law, after coming to the conclusion that the number of civil servants loyal to the Ukrainian state in Donetsk had shrunk to “an insignificant number.” Yet, for some reason, his efforts do not seem to be having much success. Earlier this year, obviously frustrated with the locals, he told reporters that even after the liberation of Donbass, and regardless of elections, Ukraine will need to “impose . . . a normal democratic agenda on those people” by having a garrison of Ukrainian troops stationed in each of its major cities.

Like other members of the Party of War, Zhebrivsky is an outspoken opponent of the Minsk peace accords. Instead of trying to put an end to the current conflict, he tells Ukrainians they should embrace “an open, serious war between Russia and Ukraine.” Despite nearly ten thousand Ukrainian casualties, and millions of refugees forced from their homes, the Party of War is quite willing to expand the present conflict, because this war is vital to achieving its ultimate political objective—gaining the unimpeded right to define who is and who is not part of the Ukrainian ethnos.