Might Is Right in Syria

Saving Syria necessitates overhauling the entire Middle East. A new political map is in order.

In the early 1940s, France—by then a stunted and drained superpower—was no longer calling the shots in international affairs. And it was doing less so in the Levant. Britain was the dominant superpower and by default the artisan of what became the modern Middle East and its Arab sovereign-states system. The Middle East polities we know today were birthed out of a defunct Ottoman Empire; they were not the handiwork of Gallic contrarians invested in a minorities policy bent on carving out the Middle East but were instead drawn by British colonial cartographers consumed by a duty to stately constancy and oneness. This vision of the Middle East as a uniform Arab world was imperial—not to say imperialist—in an eminently British fashion. It was also a model that went against the nature of the dismantled polyphonic Ottoman dominions, taking no stock of the region’s inherent ethnic, cultural, sectarian and linguistic divisions.

In the early 1940s, France—by then a stunted and drained superpower—was no longer calling the shots in international affairs. And it was doing less so in the Levant. Britain was the dominant superpower and by default the artisan of what became the modern Middle East and its Arab sovereign-states system. The Middle East polities we know today were birthed out of a defunct Ottoman Empire; they were not the handiwork of Gallic contrarians invested in a minorities policy bent on carving out the Middle East but were instead drawn by British colonial cartographers consumed by a duty to stately constancy and oneness. This vision of the Middle East as a uniform Arab world was imperial—not to say imperialist—in an eminently British fashion. It was also a model that went against the nature of the dismantled polyphonic Ottoman dominions, taking no stock of the region’s inherent ethnic, cultural, sectarian and linguistic divisions.

But as Lawrence of Arabia admitted some ninety years ago, this was the standard Englishman’s view of the world; a vainglorious illusion of an Arabic-speaking dominion, akin to some fancied English-speaking counterpart. Lawrence would incidentally go on to depict his countrymen’s conception of an “Arab Middle East” as “a madman’s notion for [the twentieth] century [and the] next.” Nevertheless, the die was cast, and an essentially “Arab” (English-designed) “Middle East” would prevail. This was a setback to France’s colonial prestige and its own vision of a region set apart by its différence; a mosaic of smaller, ethnically homogeneous and potentially less fractious ministates. This was also a blow to Near Eastern minority peoples—Alawites, Maronites, Shis and others—to whom France had issued postwar pledges of protection and guarantees of self-determination. But the rights of Near Eastern minorities were ceded to colonial prerogatives and to the English taste for uniformity and empire; la raison du plus fort est toujours la meilleure (might is always right) taught France’s celebrated seventeenth-century fabulist Jean de La Fontaine.

Under the Levantine Sun

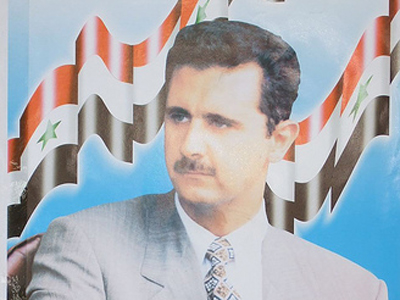

For a good part of this past year, Syria’s minoritarian rulers have put La Fontaine’s aphorism to great use. The former slaves have taken a fancy to the craft of their former masters. Indeed, despite the awesome odds stacked up against them, the Alawites have shown remarkable staying power—bloody and depraved as this might be to those unversed in the Middle East’s ways of self-preservation. But what other alternatives are being offered?

Earlier this month, as Russian and Chinese diplomats scuttled yet another U.S.-backed UN Security Council resolution meant to curb the murderous deliriums of Syria’s tyrant-apprentice, the ancient city of Damascus seemed to reemerge as the battleground of age-old communal rivalries, international ambitions and seething sectarian grudges. The early twenty-first century seems hauntingly evocative of the early twentieth. Sure, some of the actors, local and foreign, have changed, and superpowers sparring over regional influence have donned more modern colorings. But in all, little else looks any different under the Levantine sun.

Its apparent endurance notwithstanding, the history of the unitary state in Levantine societies is short and its legitimacy tenuous. A mere sixty years ago, Syria, Jordan or Palestine didn’t even exist as conceptual constructs—let alone as sovereign unitary state formations. The Middle East is inherently pluralistic and multi-ethnic. As such, it is incompatible with the demands of the unitary “national” state model as devised by early twentieth-century Britain. This is at the heart of the fault lines running through and trouncing today’s Syria. But Syria is only one example, and, as in Syria, in most modern Middle Eastern polities the sovereign state has come to incarnate the hermetic stronghold of minority rule, or else the bane of minority communities seldom attuned to the histories and ambitions of the dominant culture.

Ethnic tensions can explain more of what's wrong with Syria today than is often revealed in popular perceptions, public discourse, media coverage and academic writings. Despite the illusions of unity, the norm of Middle Eastern identities and group loyalties is division, communitarianism, diversity and fragmentation. Arabism, Arab identity and Arab nationalism are the tropes of Sunni-Arab majorities—and often theirs exclusively. These Arabisms remain largely unintelligible, unmoving and unattractive to millions of others, including Christians, Jews and heterodox Muslims whose passions and loyalties lay outside the doctrinal and emotive confines of the Arab world.

It’s the Identities, Stupid

Syria’s current Alawite rule, although professedly—and often bombastically—Arab nationalist, remains the implement of a long-hated minority’s quest for autonomy and a bulwark of its communal self-preservation. The alternative is the withering of the Alawite community or its subjugation to the tyranny of a dominant Sunni-Arab majority—something the Alawites have already made clear they will not abide. Imposing sanctions on Syria, calling for the removal of the Assad regime or dispatching foreign military expeditions will not resolve the problem. Another more nuanced approach is needed—a firm but rational one. The brutal savaging of innocent civilians must be stopped, and those meting out this slaughter must be held accountable. At the same time, traditionally maltreated Near Eastern minorities like the Alawites—but also others like the Druze, Copts, Assyrians and Shia—must be afforded avenues for unmolested group organization and political expression that safeguard their autonomy, allowing them freedoms and nurturing their distinct identities.

The principles of autonomy and self-determination proclaimed by President Woodrow Wilson in January 1918 have been trampled in the Middle East of the past century. Yet, the early twentieth-century American calls that all “non-Turkish nationalities” under Turkish rule be granted safety, security and opportunity of autonomous development can still be implemented in the early twenty-first century to the benefit of non-Arab and non-Muslim “nationalities.” Ninety years ago, President Wilson’s political advisor Edward Mandell House wrote that the British map of the Middle East has made the region “a breeding place for future war.” Issuing from the administration of an unseasoned young nation, often belittled for its shallow “sense of history,” this was a prescient call betraying subtlety of spirit, political foresight and a grasp of history that even the courtly British failed to match.

The British map of the Middle East, which has defined the region for close to a century, is an outmoded, failed model. It does not reflect a law of nature, and it does not reflect local interests or indigenous historical claims. It upholds an order that was ill-conceived and largely ill-received—in spite of its perceived endurance. It is high time this structure was replaced and future wars averted. The Middle East’s problems can still be resolved in short order, and Syria can still be plucked from the throes of civil war. But this requires foresight and strict adherence to the Wilsonian principles of the early twentieth century. Namely, this inheres remedying the cognitive dissonance that has guided prevalent attitudes, perceptions and policies toward the Middle East. The solution is a political order that valorizes the Middle East’s differences as much as it does its similarities; a new political map that preserves the region’s long tradition of religious, ethnic and cultural diversity while encouraging mutual recognition and coexistence.

Franck Salameh is an assistant professor of Near Eastern Studies, Arabic and Hebrew at Boston College and the author of Language, Memory and Identity in the Middle East: The Case for Lebanon (Lexington Books, 2010).

Image: delayed gratification